An Ancient Desert Forest

By Chris Clarke

Author Chris Clarke is a journalist, writer, activist, and co-host on the new podcast, “Ninety Miles from Needles.” Clarke has been interpreting the desert for more than 30 years. He is joined by co-host, Alicia Pike, a talented co-conspirator, and by the community of activists and others working to keep the desert whole.

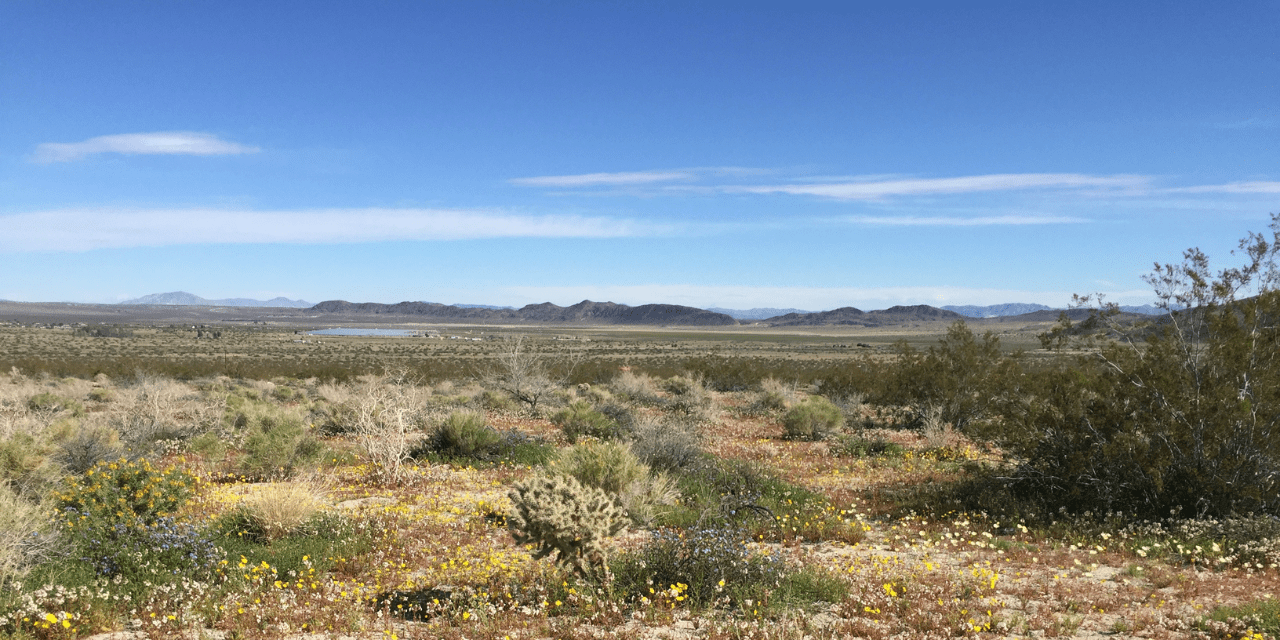

Imagine we found a country the size of France, covered in ancient forest, where trees a century old were mere saplings just getting started. Where the oldest sprouted when near-mythical monsters roamed the landscape.

Imagine visiting this country, standing in a particular spot, and watching. Perhaps you’ve left the house on an errand. Perhaps you just went out to get some air. And you walk half a block from the place you’re staying, caught up in one important thought or another, and you suddenly realize that within 60 feet of you are three trees more than a thousand years old. You turn your head and there are two more.

You start to see the open, park-like forest with new eyes, really seeing the unimaginable ancientness of it. Everywhere you look: trees 700, 1,000, 3,000 years old. Charlemagne was emperor when that tree sprouted, and that one a dozen paces east was probably sending out leaves when the Magna Carta was written. Every now and then you see a tree that could have sheltered Nefertiti, had she the airfare.

And imagine that as you really see the trees for the first time, you hear about a hundred different plans to cut them down.

It’s not that their timber is valuable, or that people need centuries-old firewood. It’s just that people have deemed this incredibly ancient forest worthless, and they’ve decided the land it occupies could be better used for other things. And so they plan to bulldoze it, stack the trees in debris piles to rot, and build their more important parking lots and garbage dumps.

This country, this forest: they exist. We live there. The trees rarely exceed ten feet in height. They are well known to science: Mojave yucca, diamond and buckhorn cholla, Mormon tea, but mostly, and almost everywhere you look below 5,000 feet in the Mojave, Sonoran, and Chihuahuan deserts, creosote.

The oldest known creosote bush, about 40 miles from my house as the raven flies, is estimated to be 11,700 years old. It’s a ring of seemingly independent shrubs. A single creosote seed germinated, its stem grew and widened for perhaps a century, then a side shoot emerged from the ground next to the original stem. It grew. Side shoots emerged. After another century or five, the oldest stems began to die, leaving a widening hole in the clump of stems.

That 11,700-year-old creosote, which for a tiny fraction of its life has been known as King Clone, expanded outward across the Mojave landscape at an average rate of three quarters of a millimeter per year. It’s not the only creosote that has done so. On a typical walk in my neighborhood I pass within stone-throwing distance of two or three dozen smaller rings, some of them ten or twelve feet across at the soil. Some have open soil in their centers. Others have not yet cleared the dead stems from their hearts.

Do the math and use a much more conservative millimeter per year to defend against charges of hyperbole, and that’s 300 years of age for every foot in width of those rings. Creosote stands in excess of 500 years old are as common as dirt here. A ten-foot clump of creosote may have germinated about the time David threw his stone at Goliath, a 12-foot clump before people in Japan started growing rice.

I have been thinking these days about a particular large-scale plan to convert much of the California desert to renewable energy generation plants. This plan has been a decade in the making. It is controversial, but it is getting less so as the years pass. There are provisions in this plan to set aside wide swaths of the California desert for conservation, in arrangements as permanent as anything can be when it’s the U.S. government doing the arranging. There are provisions to protect certain threatened species, and to preserve habitats that are rare or ecologically important or which possess the ineffable characteristics of wilderness.

And so many have been persuaded to support the plan, which trades those protected areas for freedom to convert a large number of square miles of desert deemed to have no wilderness characteristics, lesser ecological significance, fewer endangered animals, fewer rare plants.

Creosote is the most common woody plant in the Mojave. No one fears its extinction. In this renewable energy plan, creosote is mentioned primarily to identify the kind of habitat it dominates. It is not a special status species; it is barely a regular status species. It is ubiquitous and environmentalists peer through its branches hoping to see something interesting on the other side.

I have seen creosote rings 1,500 years old on the footprints of proposed desert solar facilities, at the verges of dirt roads in off-road vehicle sacrifice areas. I have seen them bedecked with discarded plastic bags in vacant lots next to chain drugstores.

They make up the only ancient forest I’ve ever heard of that no one can see, though they look square at it.

I see this forest now, and it tears my heart. And once seen, it cannot be unseen.