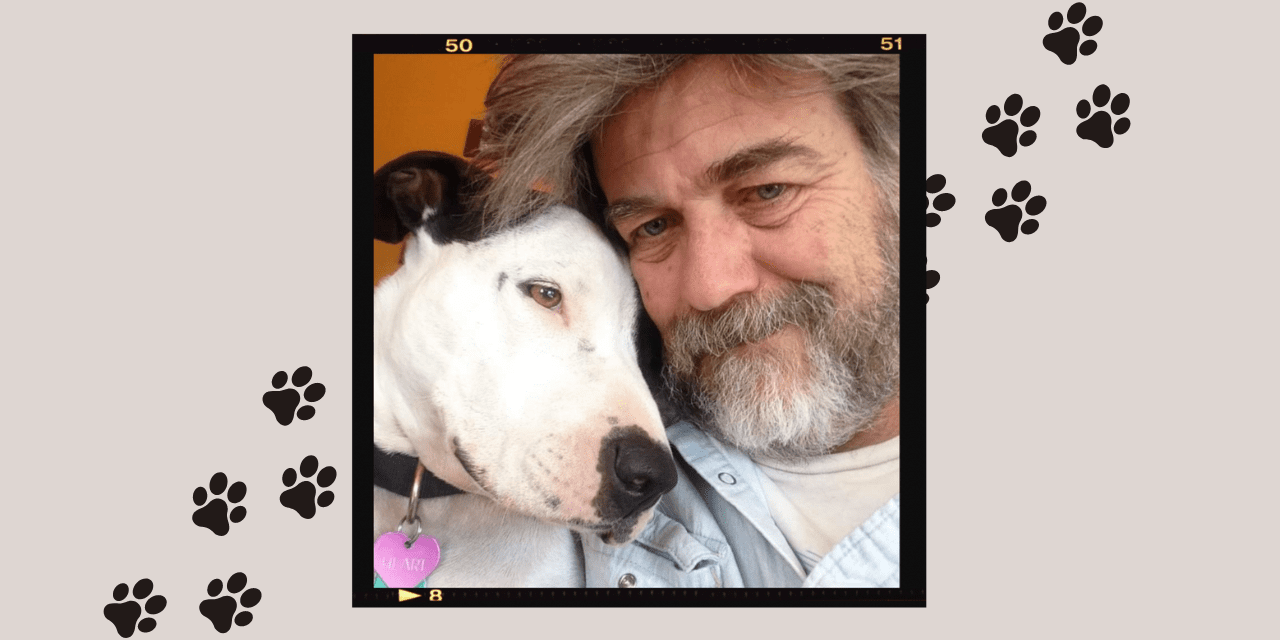

Walking With Heart

By Chris Clarke

Author Chris Clarke is a journalist, writer, activist, and cohost on the new podcast, “Ninety Miles from Needles.” Clarke has been interpreting the desert for more than 30 years. He is joined by co-host, Alicia Pike, a talented co-conspirator, and by the community of activists and others working to keep the desert whole.

I couldn’t tell where the feathers came from. There were no trees, no power poles, or other perch from which they might have descended; just the bare Mojave Desert sky, uncharacteristically overcast. There were four of them, then six, then a dozen, arcing and twirling lazily toward the ground.

Had a peregrine or a prairie falcon swooped and caught one of the Eurasian collared doves that flock in my neighborhood, knocking a few feathers loose from its inflight prey? Had a hawk’s talon scraped them off a quail’s breast? I glanced at my dog, Heart, at the other end of the leash, briefly imagining she would nod, mutter, “huh,” and confirm the oddness. But she was lost in thoughts of her own, sniffing after side-blotched lizards beneath the desert milkweed.

The feathers were beautiful and plain, a dun-gray color slightly darker than the sky, each of them the length and width of a fingernail. They pirouetted and eddied in the light wind. I craned my neck again to find where they’d come from. I failed again.

Sometimes the small pieces of a desert life provide their own creation myths. Sometimes they don’t. Walking a few days beforehand, Heart had doubled back forcefully to sniff at a bit of fluff. It was downy rabbit fur, and the sticks were spattered with gore, and a pile of coyote scat lay nearby.

“Clearly, Holmes,” I explained to Heart, “an unfortunate hare happened upon this sample of coyote dung, sniffed at it, and exploded.” She gave me the merest ear flick.

One morning when she was new to me, that odd Mojave overcast having reached its full and appropriate flower as a slow, soaking rain, we walked out at 8:30 in the morning. I had my phone to my ear. I talked with a close friend as we walked. A mile from the house, Heart froze at roadside, stared off into the creosote. I didn’t see why for a few long minutes, but I was distracted and glad to stand. It took a moment for them to resolve out of the blur of creosote and fog: a pair of coyotes, then three, then four, out doing a few late morning rounds under cover of the sheltering gloom. One of them, a seeming youngster, approached to within 20 yards of Heart in apparent guileless curiosity. A moment of curious air sniffing for both young dog and young coyote passed, and then the wild ones loped casually across the road in front of us and into the National Park.

Phone to my ear, I would have missed them if not for Heart, wholly in the present as dogs always are.

Heart has spent at least a half hour a day since 2014 encouraging me in one way or another to put down the phone, to step away from the screen. When she persuades me, which is about a third of the time, being away from screens has been instructive. I have felt more hopeful. I have felt invigorated.

Mainly, I have felt less cynical.

If you were to sum up the usual mood of the Internet as a whole in a single word, the word would have to be “cynical.” Cynicism is a suit of armor. If a video or a piece of writing threatens to teach you something new and uncomfortable, you can just dismiss it by arguing with the headline. No need to actually click away from Facebook and read the thing. (When I link to our podcast on social media, comments pile in making criticisms that are actually addressed within the first few minutes of the episode. Talk about incurious.)

Modern cynicism defends itself by casting itself as the only intelligent alternative to mawkish sentimentality. But in truth, it’s only the mawkish sentimentality that cynics allow to survive. A video of a kitten giving a mastiff a shoulder massage will go uncriticized. So will a mass and useless catharsis over the political tragedy du jour, drip with sentiment as it may. As long as sentiment is utterly powerless to change anything, cynics like it just fine.

Sentiment with force behind it? That’s different. Develop a passion for a particular place, or a cause, or group of people, and harness that sentiment to protect what you love, and you will be tweaked for caring too much. Caring too much about an issue makes the cynic tired. It makes the cynic defensive against the possibility that his or her life is lacking something essential. Hackles will be raised. Suggestions will be offered that you get a life, that you have too much time on your hands.

Personally, I’m thinking cynics have not enough time on their feet.

Ed Abbey wrote that “sentiment without action is the ruin of the soul.” He had a fair point. Sentiment devoid of the power that passion brings accomplishes little. It may be, like that quadrant of the Internet devoted to pictures of cats, of momentary value for entertainment and distraction, which few would argue we don’t need.

But sentiment without action, sentiment without passion, bolsters cynicism. It reinforces cynicism. It justifies cynicism. And cynicism is the off-road vehicle of the soul. It selects a goal and bee-lines toward it, heedless of what lives along the path. Cynicism is incurious. It obliterates nuance, breaks the branches of actual living detail as it roars past, then reaches its destination and declares there was nothing worth noting en route.

Yee haw. And yet the cynics miss the drifting of coyotes across their path, the unexplained showers of odd feathers. I could not give those up for anything.