Is the desert getting the cold shoulder from the State of California?

By Chris Clarke

Chris Clarke is a journalist, writer, activist, and co-host on the new podcast, “Ninety Miles from Needles.” Clarke has been interpreting the desert for more than 30 years. He is joined by co-host, Alicia Pike, a talented co-conspirator, and by the community of activists and others working to keep the desert whole.

The state of California is working hard to figure out how to conserve 30 percent of the state’s land by the year 2030 – but the desert is being given the cold shoulder in the process.

The California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA) is shaping the state’s so-called “30 by 30” process by way of a “Pathways” document, which is being built in a cumbersome process that on the surface includes a great deal of opportunities for public comment. In reality, those opportunities are weirdly limited, restricted to public meetings held online during business hours, or by way of written comments that can be submitted through an opaque process. You can’t really fault the CNRA for this: it’s essentially standard operating procedure for agencies these days to be really bad at soliciting and receiving public opinion.

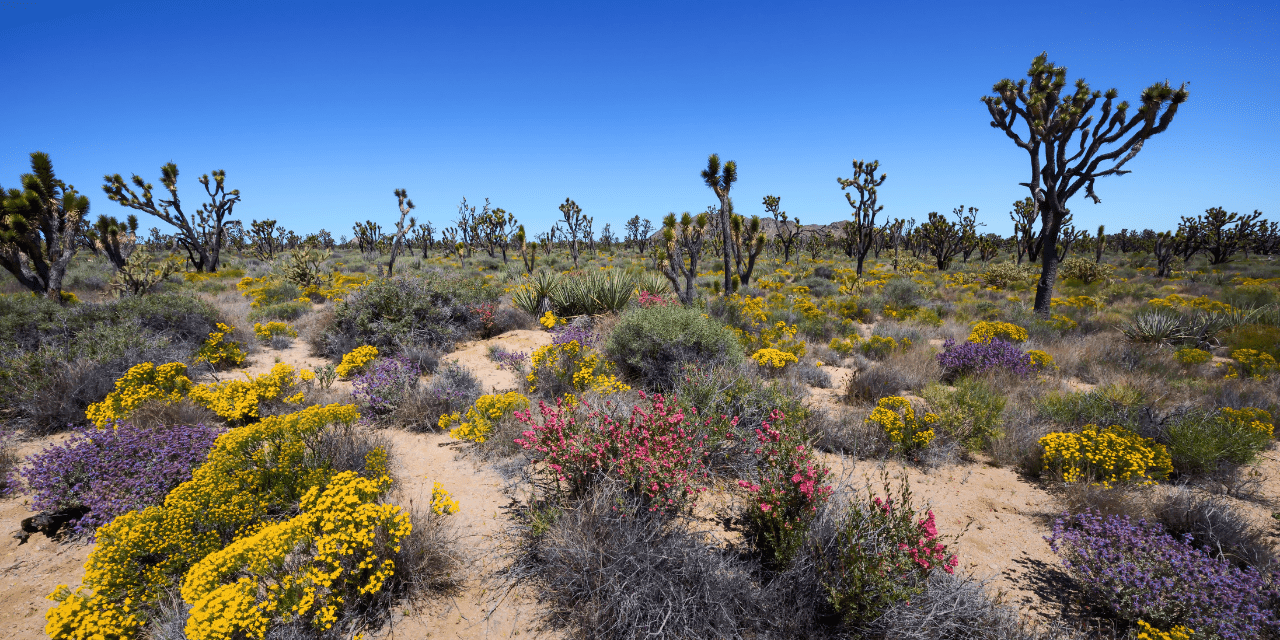

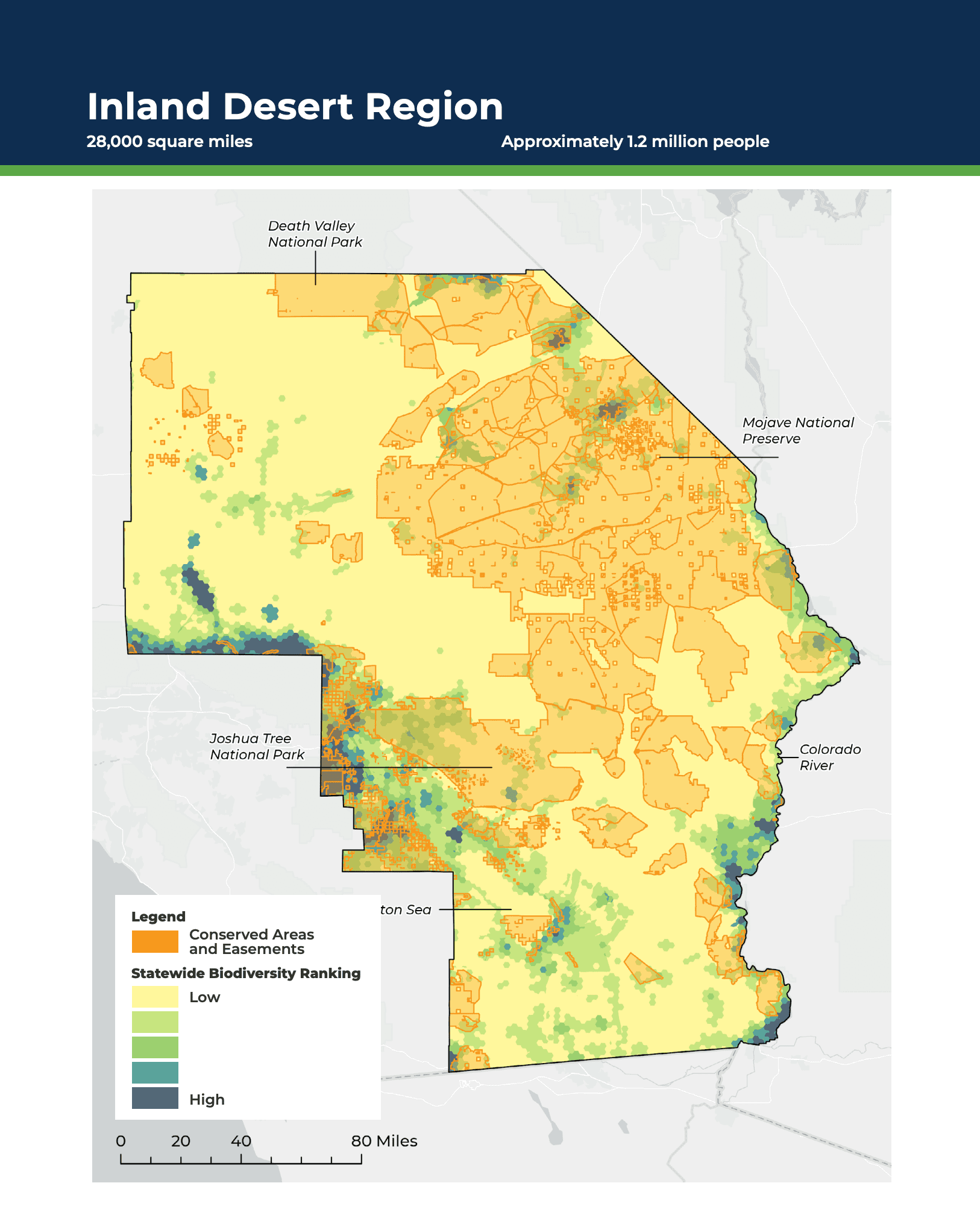

For desert residents, the range of problems with the Pathways document is broad enough that you’d need a whole series of meetings to sort them out. For one thing, the Pathways document relies on badly outdated science in its claims about the desert. California’s deserts, covering 28 percent of the state’s land area, are home to 38 percent of the state’s plant species. Over the last several decades more and more species of plant, insect, and reptile have been discovered in California’s deserts. Fifty species of mammal are found in just Joshua Tree National Park. And yet the Pathways document includes maps (one shown) seemingly based on 1969 data that describes the state’s deserts as having “low biodiversity.”

Since biodiversity is essentially the number of species in an area, the Pathways document including these maps is badly flawed.

You’ll notice I said “maps” in the above paragraph. There is no one map describing California’s deserts in the Pathways document. CNRA has split the state up into regions to consider one at a time, and the desert doesn’t get its own. There is one region, Inland Deserts, that includes all of Imperial County and the desert portions of San Bernardino and riverside counties. That leaves out a lot of desert. Where did the rest of it go? It’s lumped in with non-desert places in three other regions. Death Valley and the Kern County desert are lumped in with the Sierra Nevada. The Antelope valley is grouped with Los Angeles. And Anza Borrego, that wealth of Sonoran Desert species, is tacked onto the San Diego region. Essentially the state has split things up along county lines, as if Tecopa had more in common with South Lake Tahoe and Alturas than it does with Baker.

Meanwhile, the coast north of Santa Barbara gets three regions all to itself, despite there being substantial similarities between them all.

I’ve been peripherally involved in discussions with state agency scientists on topics like carbon sequestration in desert soils — in other words, how those soils lock up greenhouse gases and help us curb climate change. Local scientist Robin Kobaly has been doing some amazing research on the topic. She has helped document how intact desert vegetation works with mycorrhizal fungi in the soil to take carbon out of the atmosphere and deposit it as calcium carbonate, a.k.a limestone or caliche, in the desert soil. This process gets a boost from rainfall, which soaks dissolved CO2 down into the desert soil where it can combine with calcium, with or without the help of desert plants. And yet the CNRA scientists refuse to consider the desert’s soils as significant reservoirs of sequestered carbon, which is one of the things the whole 30 by 30 process is supposed to focus on.

I wish I could say this was surprising. But the state of California has long regarded its deserts, and those of its neighboring states, as broken, barren wastelands good only for dumping trash or scraping for raw materials, or as a no-holds-barred wild west playground. That attitude is changing, as increasing numbers of Californians have learned that desert ecosystems are unique and diverse, and offer potential answers to some of the toughest problems we will face as the planet warms.

It’s just a shame that when it comes to understanding the desert, the state’s natural resource agency lags so far behind the people of the state.

As always, our podcast, 90 Miles from Needles, hopes to fight that kind of misinformation by sharing stories about the wonderful living things, including humans, to be found in our deserts. Maybe the state will catch up eventually.