STAGECOACH 2022: Taking Passengers on a Parallel Path to a More Inclusive America

By Bruce Fessier

A stocky white guy in his late 30s was swaying to the music at the recent Stagecoach festival with a disturbing message on his back:

“This is our F… country,” his t-shirt said. But, instead of the ellipses, an image of a U.S. flag followed the “F,” as if to re-write Woody Guthrie’s anthem as, “This land is made for ‘F-ing’ people like me.”

Some could have perceived it as a statement from a white supremacist.

But the man was moving to the music of Smokey Robinson, the premier songwriter for Motown; the record label that turned what was once called “race music” into pop music in the 1960s.

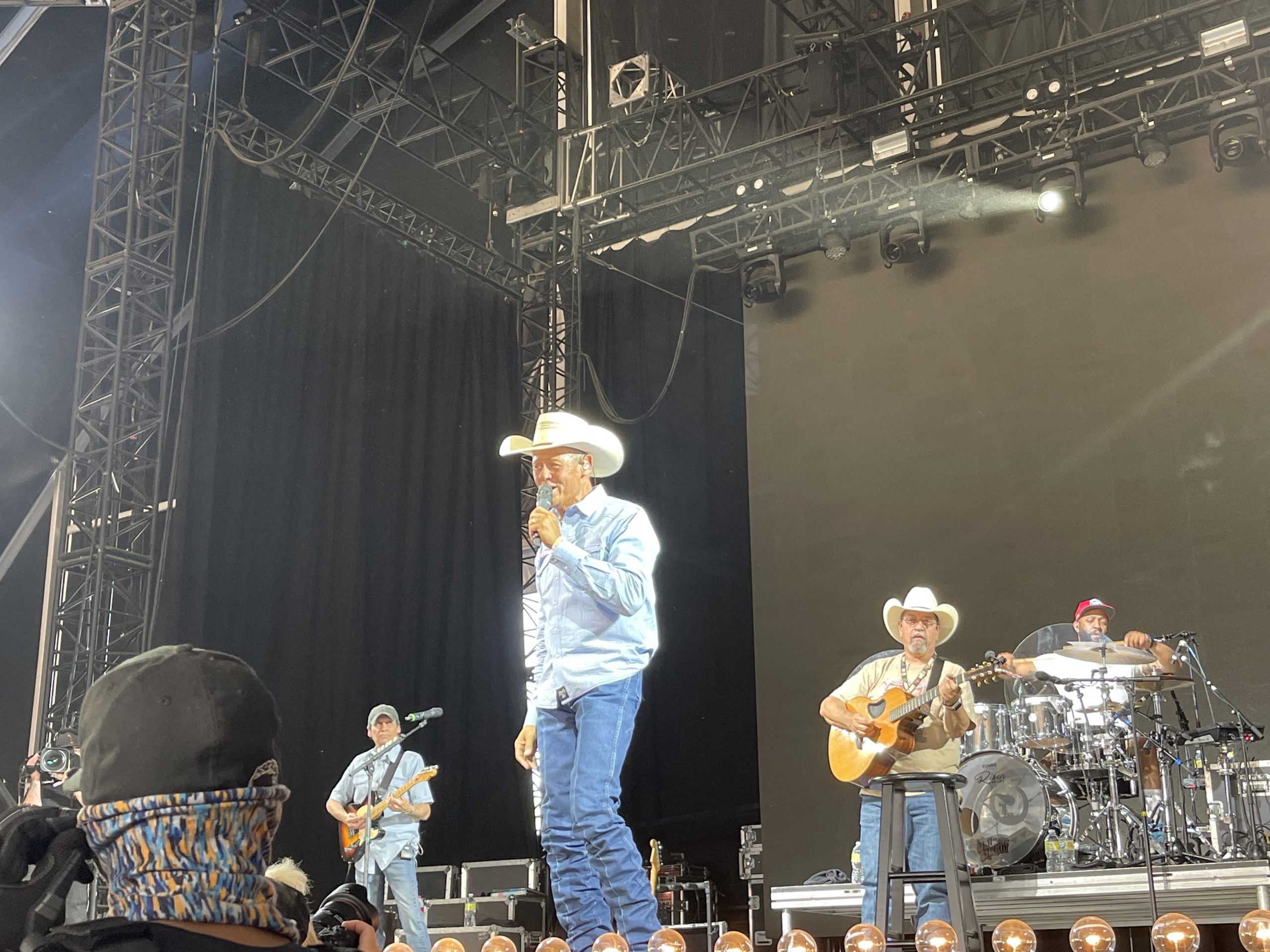

Robinson, 82, grew up in Detroit when dining and entertainment venues were segregated, and schools were “separate but equal.” His “You Really Got a Hold on Me” was on the charts in 1963 when Motown recorded Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech at a march in Detroit. It was released it two months later when King delivered a more famous version of the speech at the March on Washington.

And now, on a warm Sunday evening in this Palomino tent at Indio’s Empire Polo Club, a white flag-appropriating Smokey Robinson fan was proclaiming, “This is our country.”

That’s when it became apparent Stagecoach had changed. This festival founded as a complement to Goldenvoice’s hipper, more inclusive Coachella was suddenly reflecting the changes in our country.

Robinson’s appearance in a sexy buttoned-to-the top black shirt and print jacket wasn’t the first sign of the festival’s cultural evolution. Stagecoach announced earlier that “divisive symbols,” including Confederate flags and “racially disparaging or other inappropriate imagery” would be banned. So, t-shirts with cringeworthy messages were largely absent from merchandise booths.

But this Stagecoach lineup, curated by Goldenvoice festival director Stacy Vee of Rancho Mirage, included more women, more African Americans, and more members of the LGBTQ community.

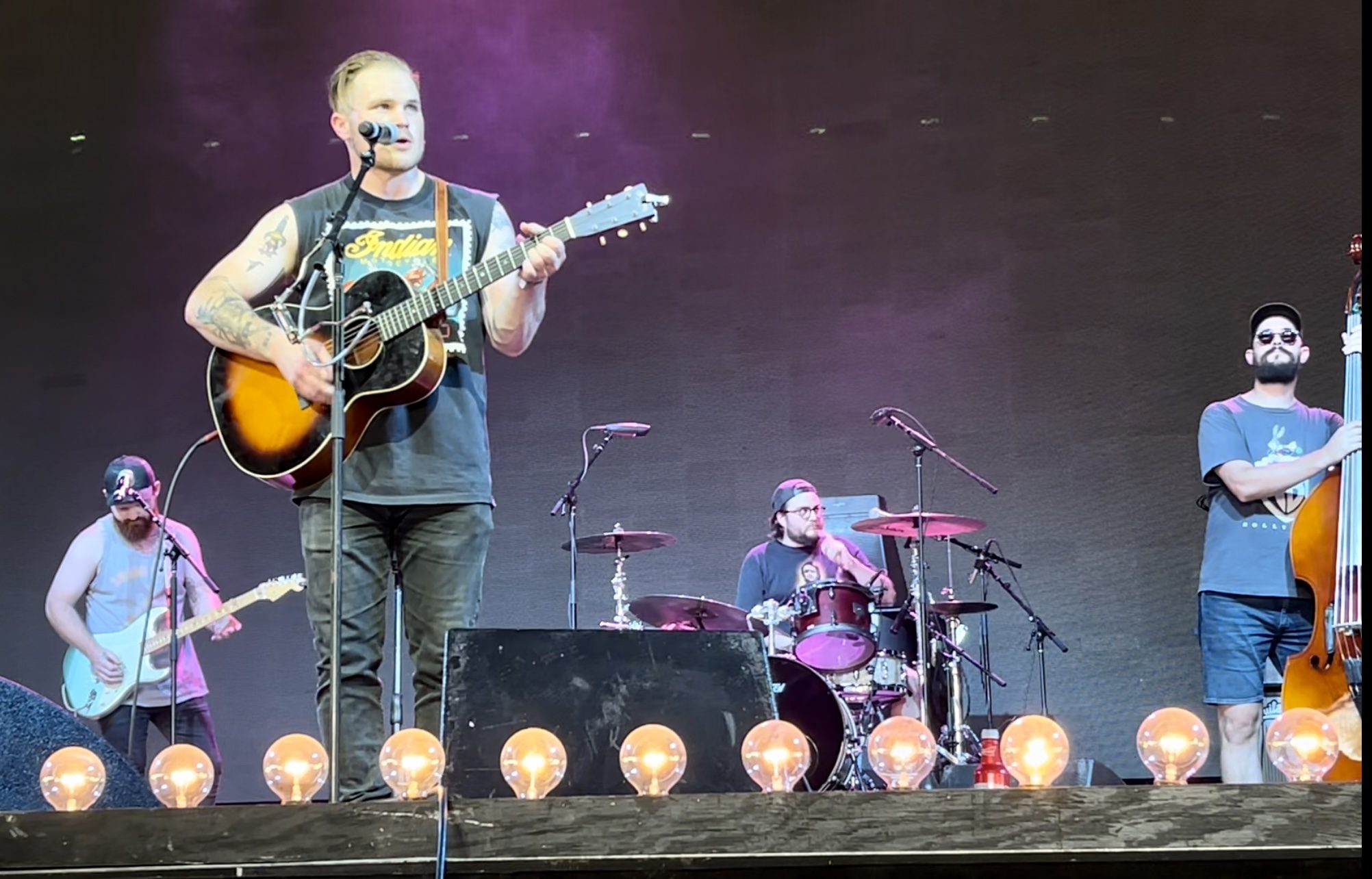

T.J. Osborne of the Osborne Brothers band noted Saturday, April 30 on the Mane Stage that “a lot has changed” since 2018, when the duo gave what he called “a terrible” set at Stagecoach. Earlier that month, the brothers won a Grammy Award for a song T.J. wrote after coming out in Time Magazine in 2021. The lyric to “Younger Me” said, “Didn’t know that being different/ Really wouldn’t be the end.”

Now he was introducing the song to a crowd of at least 75,000 people by saying, “There’s been a lot of preconceptions about country music fans. But, for thousands of you all to come out here, watching me, a gay man, perform tonight… This is incredible.”

Stagecoach has been showcasing female artists since Goldenvoice president Paul Tollett founded the festival in 2007. The names Miranda Lambert, Sugarland, and Sara Evans appeared above Willie Nelson’s on that first poster. Taylor Swift, Tricia Yearwood, and The Judds, whose matriarch, Naomi, died before Saturday’s Stagecoach began, were featured in the 2008 event, along with the Eagles.

Carrie Underwood also debuted at Stagecoach in 2008 and she returned Saturday night to provide the most momentous set of this festival.

Underwood, who has uncommon range and vocal purity, performed with more animation, athleticism and theatrical bells and whistles than at any of her three previous Stagecoach appearances.

Teaming with a Black choir on her classic, “Jesus Take the Wheel,” she seemed to be approaching Beyonce´ levels when she segued into a soul-stirring rendition of the gospel standard, “How Great Thou Art.” She followed that by dedicating “See You Again” to Naomi Judd, keeping it emotionally honest by turning it into a “human experience we can all share.”

But, three songs later she brought out frickin’ Axl Rose. The Guns N’ Roses front man, appearing in torn blue jeans, boots, and short blond hair, had to keep up with Underwood’s energy on “Sweet Child o’ Mine” and “Paradise City.” But the sum of these two diverse parts, and the surprise of seeing them together, created the powerful equivalent of a Coachella moment – with Stagecoach panache.

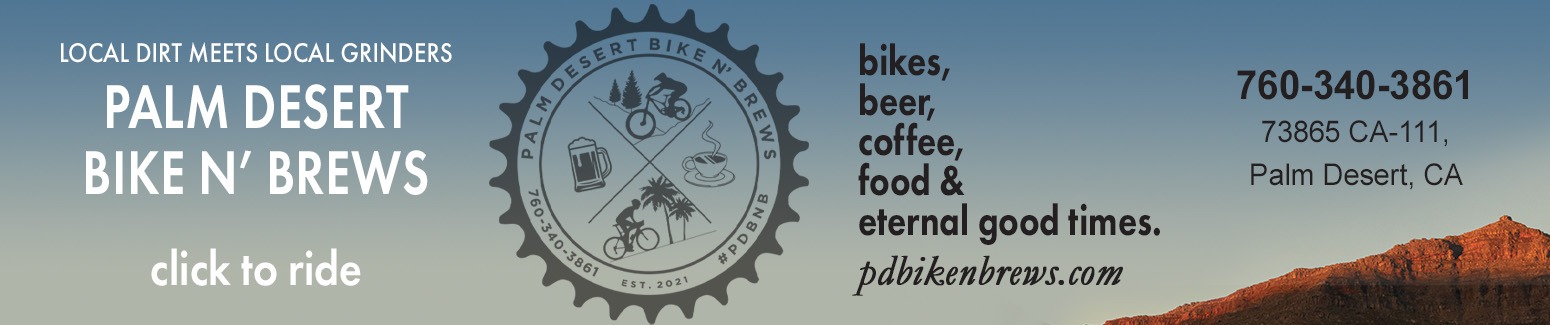

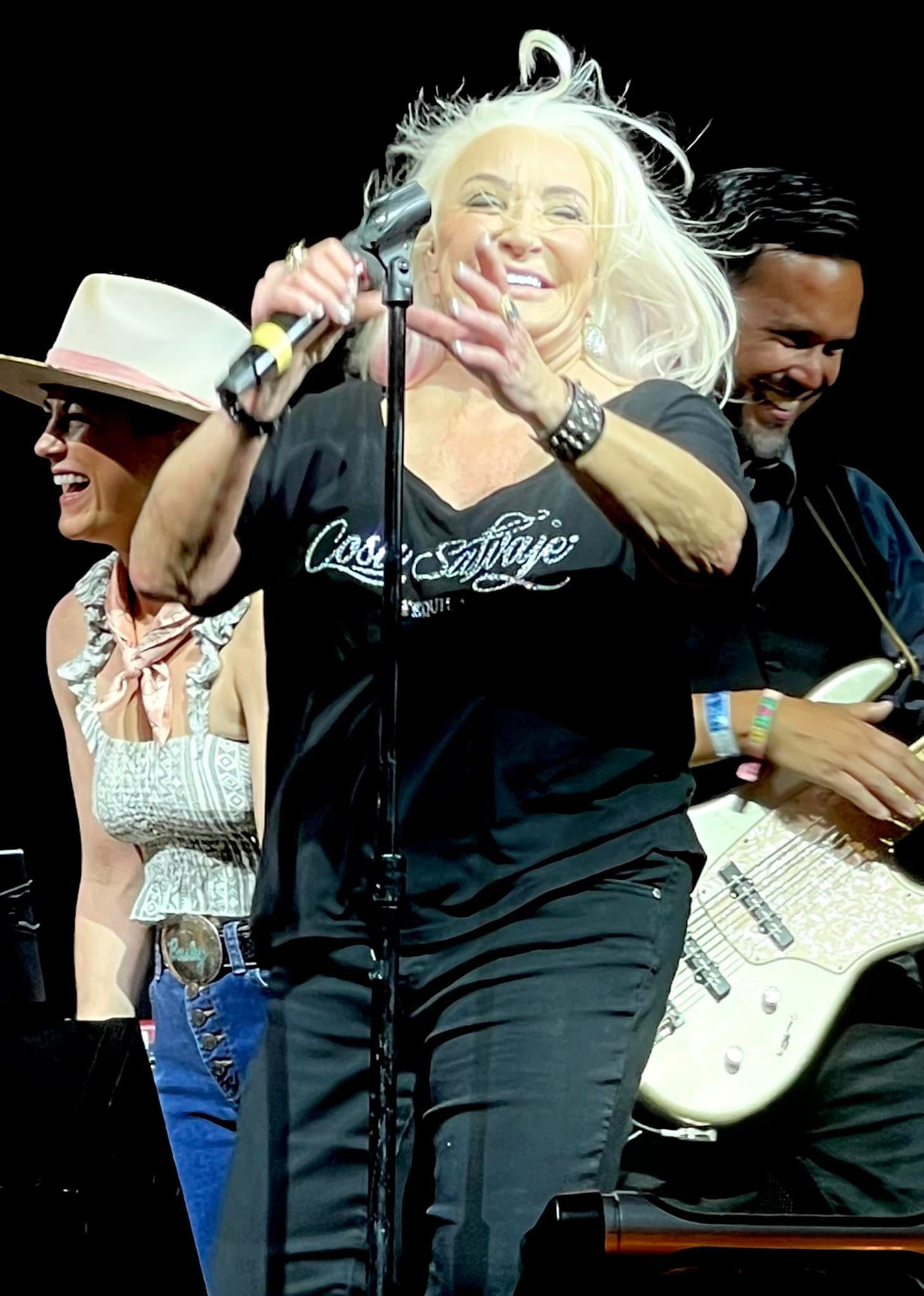

Seventies teen sensation, Tanya Tucker, provided another collection of Stagecoach moments after stepping into a Friday slot intended for Brandi Carlisle (who tested positive for COVID-19 the day before), turning it into a celebration of life’s ups and downs.

Tucker, who won a Grammy with her 2019 comeback album, “While I’m Living,” received a rapturous response to another comeback hit, “Love Me Like You Used To” from 1987, which moved her deeply.

“I don’t know how to answer that,” she said. “It’s hard for me to believe that anyone would want to watch me. Somebody must have put something in your drink!”

She name-checked some legends she’s worked with, including Lambert and Loretta Lynn, the 90-year-old coal-miner’s daughter who played the 2011 Stagecoach. Then she called Carlisle on Facetime, letting the “Broken Horses” artist see the humongous crowd turn its affection toward her. Tucker stoked the burning love by calling Carlisle “the greatest female singer that ever walked the earth.”

Maren Morris provided a more typical Stagecoach moment when she brought out her husband, earlier Mane Stage performer Ryan Hurd, to sing their hit, “Chasing After You.” That wasn’t a big surprise, but it kept Morris on her trajectory towards a headliner slot – along with such other women at Stagecoach as Lainey Wilson, who performed on the small, unshaded SiriusXM Spotlight Stage just weeks after winning three Academy of Country Music Awards, including Song of the Year for “Things A Man Oughta Know.”

Margo Price, 39, may never get that Mane Stage headline slot – not with Dolly Parton and Kacey Musgraves also waiting for their shots at the pinnacle of America’s most popular country festival. But Price’s breakout in the Palomino tent reinforced how passionately Stagecoach fans embrace astounding female performances.

In just her second Stagecoach appearance (following a 2017 set lost in the shadows of Morris, Shania Twain and Elle King), Price made one of the great entrances in Stagecoach history – riding up to the Palomino tent on a horse, taking a guitar like a handoff from a quarterback and stalking on stage to say, “Hello Stagecoach.” Her thin voice belies the power she brings through sheer attitude and irony, which was personified in her opening number. Her all-male band, featuring four guitarists, blazed through her 2020 country rocker, “Letting Me Down,” as Price sang the nuanced chorus, “You got away/ you got a way/ of letting me down.”

She deadpanned, “We do country for people who do psychedelics,” which is why she’s better suited for a Gram Parsons Cosmic American Music Fest than the Mane Stage at this point of the festival’s growth.

Thirtysomething white male cowboys are still the marquee stars at Stagecoach. Thomas Rhett and Luke Combs, the opening and closing-night headliners, delighted the massive crowds by riding the high-energy, big production horses that got Stagecoach to where it is today via acts like Luke Bryan, Jason Aldean and Dierks Bentley headlining previous Mane Stage bills.

The Black Crowes, featuring the fiftysomething Chris and Rich Robinson brothers, made Stagecoach history by performing their fusion of Southern and grunge rock instead of modern country on the Mane Stage. But, even with a second lead guitarist and two female backup singers to add depth to just some of their rock hits, including “Jealous Again,” “She Talks to Angels,” and Otis Redding’s “Hard to Handle,” the Black Crowes sounded off-Broadway on a Broadway stage for cowboy musicals.

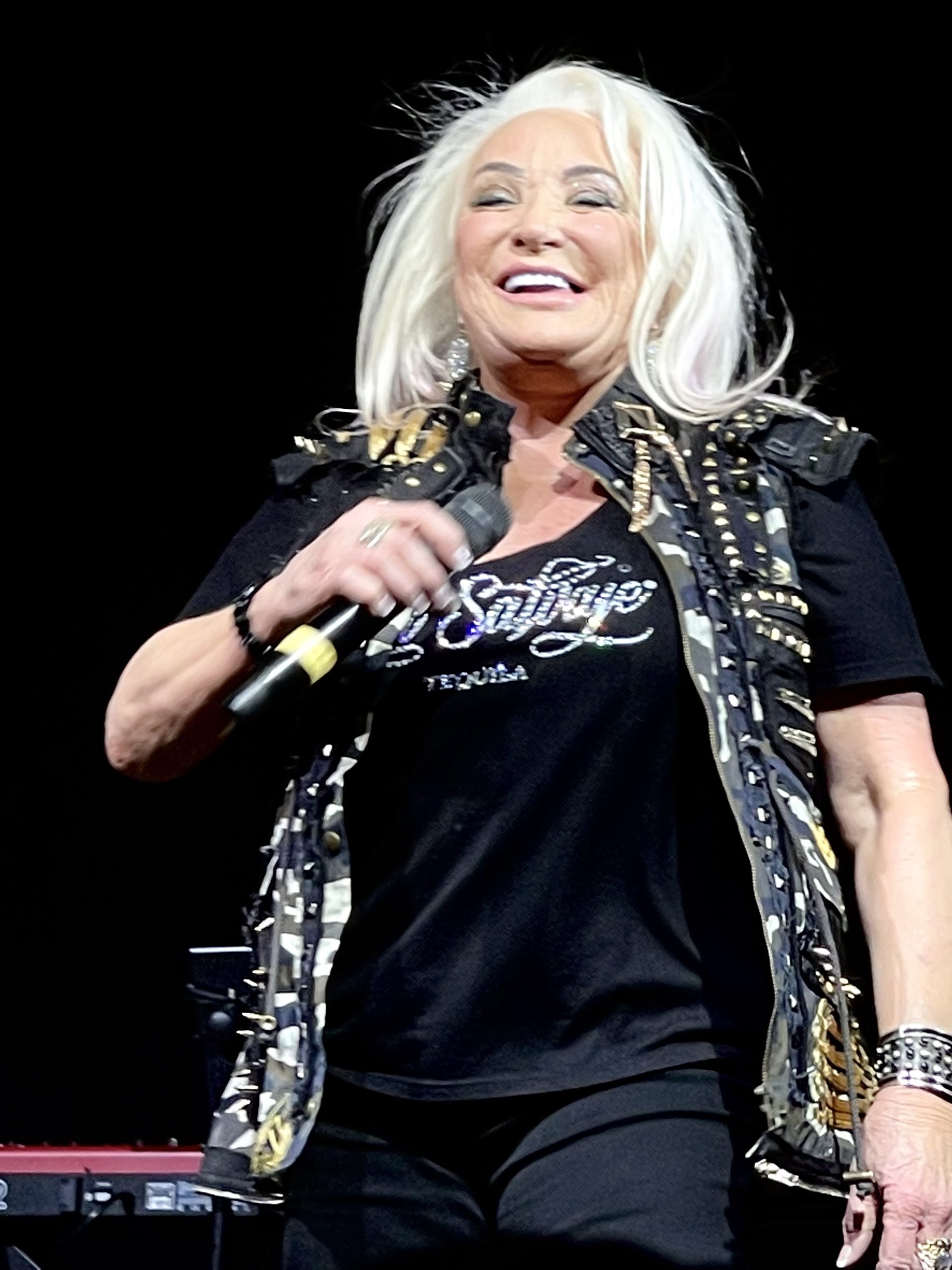

The Marcus King Band best exemplified the male rock guitar-jam sound the Palomino has become famous for through previous appearances by Lynyrd Skynyrd, Gregg Allman, ZZ Top and Molly Hatchet. Strains of the Allman Brothers sound seeped into their extended songs, but their arrangements, featuring dual lead guitars, horns, and a Hammond B3 organ, were so organically contagious, the packed early-evening crowd sang along even to their new song, “Hard Working Man.”

Country veteran Neal McCoy had just as many sing-alongs in the preceding Palomino set with his fun, incongruous covers of past Black pop hits like Michael Jackson’s “Man in the Mirror” and Bruno Mars’ “Uptown Funk.” But the Marcus King Band, led by the 26-year-old student of jazz from the Greenville Fine Arts Center in South Carolina, elicited a passionate response more purely on the greatness of his band’s cohesion and musicianship.

Recently honorably discharged Navy veteran, Zach Bryan, and LOCASH (Chris Lucas and Preston Brust – a duo that co-wrote Keith Urban’s “You Gonna Fly” and Tim McGraw’s “Truck Yeah”) seem primed to climb the Mane Stage ladder. LOCASH brought out Mike Love, Bruce Johnston and three touring members of the Beach Boys to harmonize on LOCASH’s new single, “Beach Boys.” The legendary surf band also joined the duo on two of its own classics, “Fun, Fun, Fun” and “Kokomo” — an imaginary city in Beach Boys lore, but with the real Indiana hometown of LOCASH vocalist Brust.

LOCASH also seems to have the support of California culinary magnate Guy Fieri, who now interviews select artists from the tent where he reigns over the Stagecoach food scene.

But the progress of female performers indicates it’s time for a first-ever lineup with two women at the top of the bill. Or maybe a Black headliner. Or a multiracial band. Singer-guitarist Lindsay Ell played the Mane with a bi-racial group and delighted audiences, shredding her guitar like a rock goddess.

Smokey Robinson wouldn’t have been such an important addition to the Stagecoach legacy if it hadn’t been for all the other great African American acts in this year’s lineup. He might have just continued Stacy Vee’s tradition of showcasing ‘60s legends, such as Tom Jones, Eric Burdon, and the Zombies, if he hadn’t been preceded by so many other amazing Black singers and rappers.

Yola, one of three performers to play both Coachella and Stagecoach, along with Canadian country star Orville Peck, and electronic artist Diplo in late-night slots, immediately connected with her Palomino audience on “Barely Alive,” asserting, “I been here, and I know how it is/ I been living it alone for all these years/ Isolated, we hold in our tears/ And we try to get by.”

That 2021 Dan Auerbach-produced mid-tempo ballad could have reflected surviving the pandemic, and Yola could have been another of the many artists saying how great it was to be on the other side of the global disruption. But her Black rootsy repertoire brought new meaning to feeling the pain of isolation.

The big-voiced Brit filtered her songs through her Bristol view of African American singers such as Odetta and Nina Simone, and synthesized it into something altogether different, and appealing to her Stagecoach audience. Her finale, “Stand for Myself,” felt like a civil rights anthem by an outsider beginning to sense what it must have been like to refuse to move to the back of the bus. Conversely, her performance of Elton John’s anthem, “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” expressed what it must feel like for a roots artist to suddenly get nominated for six Grammy Awards and be cast in the upcoming Baz Luhrmann film, “Elvis.”

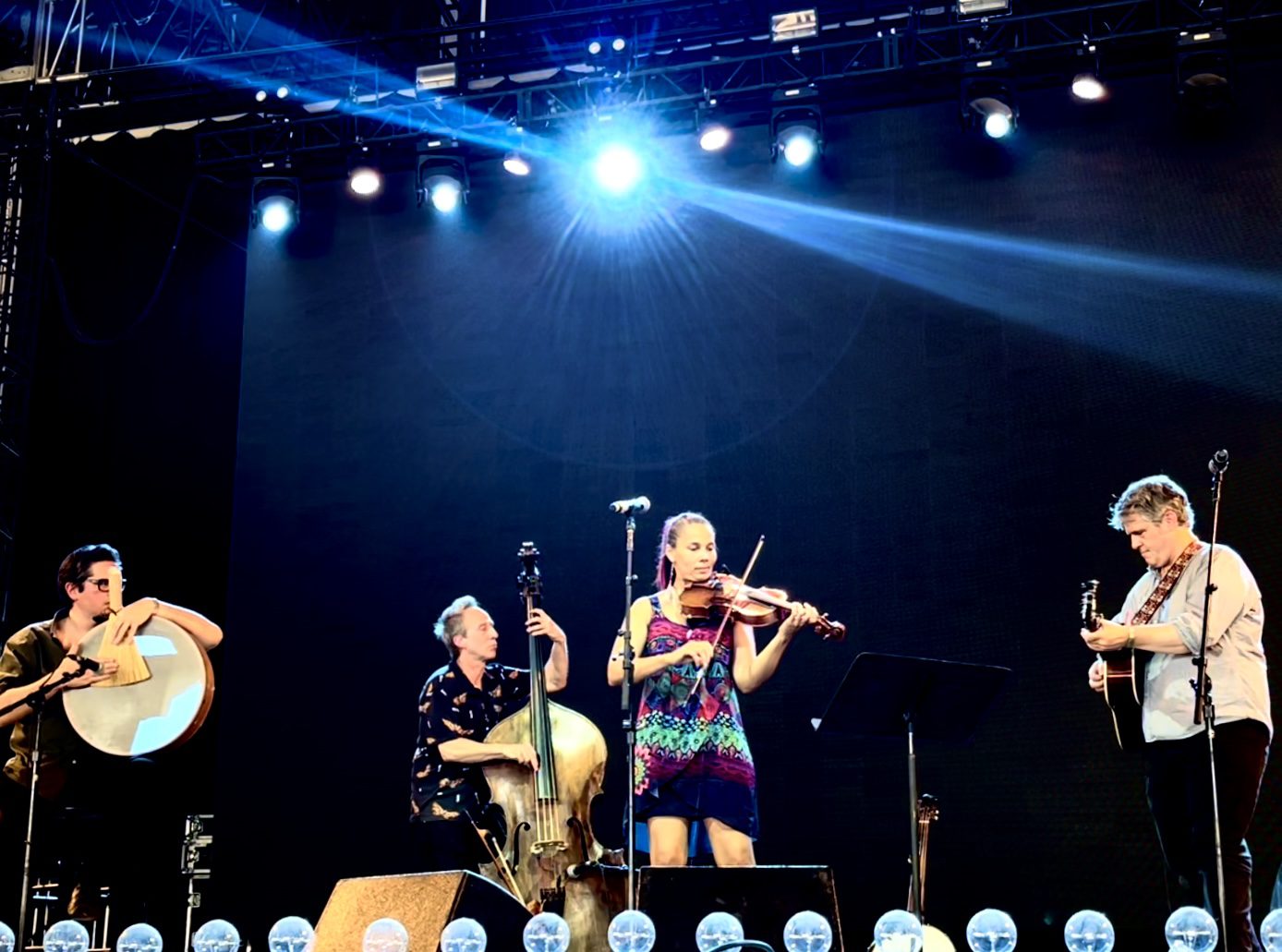

Less than two hours earlier, Rhiannon Giddens gave an insightful complement to Yola’s set. Giddens, a Greensboro, North Carolina native, studied opera at Oberlin College in Ohio and founded the Grammy Award-winning Carolina Chocolate Drops, which caused a buzz at the 2008 Stagecoach with its old-timey material. She has lived the Southern Black experience and she proved capable of great feminine power in songs like “(I’ve got your picture) She’s Got You.” But she also conveyed her studies of music and anthropology. This back-to-back combination of insider-outsider relationships to the American roots movement was a remarkable juxtaposition.

But that was hardly the extent of the Black experience at Stagecoach.

The festival literally began for me at 1:30 p.m. Friday in the Palomino tent with a performance by Amythyst Kiah, another Southern roots singer-guitarist who studied Bluegrass, Old Time, and Country Music at East Tennessee State University. Kiah, who includes Radiohead’s “Fake Plastic Trees” in her repertoire, was more introspective than she might have been with a larger, later audience, but she connected on her performance of “Natural Blues” and “Black Myself,” both remixed on records by the electronic legend, Moby.

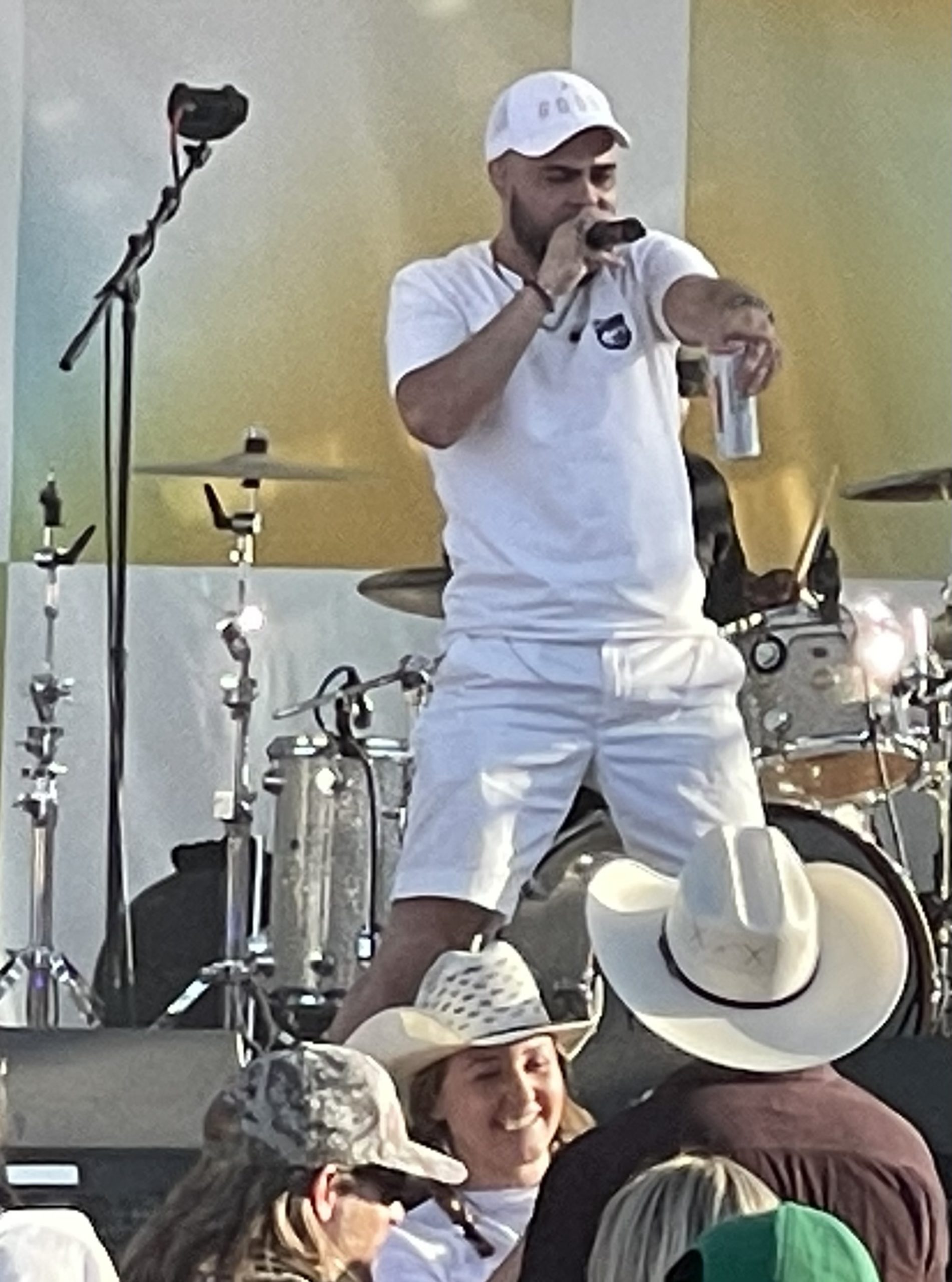

Shy Carter, who recorded “Stuck Like Glue” with Sugarland, provided a totally different African American fusion on the Spotlight and the Bud Light Seltzers stages. His vocals with a Black drummer and bass guitarist mixed old-school rap, R&B, and country. But he directed his music to specific women at the intimate Bud Light venue and it went over like Elvis Presley handing out scarfs to his fans.

All of this led to Smokey Robinson being the last African American to perform at Stagecoach. In this context, his appearance was not incongruous with the Stagecoach past. It was a sustained celebration of Black artistry and the Palomino audience completely accepted him as music royalty. A projection called Robinson “America’s greatest living poet,” and no one could argue — partly because we had seen the roots of ‘60s Black music and partly because Bob Dylan had declared that.

Opening with his 1981 hit, “Being with You,” Robinson set the tone for his show and perhaps the entire festival with the words, “I don’t care what they think about me and/ I don’t care what they say… I don’t care about anything else/ But being with you.”

The audience sang along with Robinson’s soundtrack to a generation that was once even more divided than we are now. The mostly white crowd seemed to feel the tracks of his tears personally.

It would be nice to see more Mexican-American music at Stagecoach because it’s so embedded in the California country culture. Raul Malo sang in Spanish during a great Americana set by the Mavericks, but he’s of Cuban heritage from Miami. The bilingual Giselle Woo and the Night Owls of the Coachella Valley would provide that inclusiveness, creating a compelling bridge from their recent Coachella appearance.

But seeing white country fans wave their cowboy hats and thump their hearts in support of Smokey Robinson was a big step forward for Stagecoach. Its many diverse moments added up to a feeling that maybe we’ve emerged from the COVID pandemic to find a light outside of a long tunnel.

It felt like a glimpse of the America we would like our country to be.

Bruce Fessier has covered Goldenvoice festivals for over a decade for the Desert Sun and has since written about his experiences for Palm Springs Life and Inland Empire Polo Club magazine. Fessier has long been covering historic music in the desert, including our hometown legends. Joshua Tree Voice is honored to publish the contributions of this Coachella Valley Music Awards Lifetime Achievement honoree.