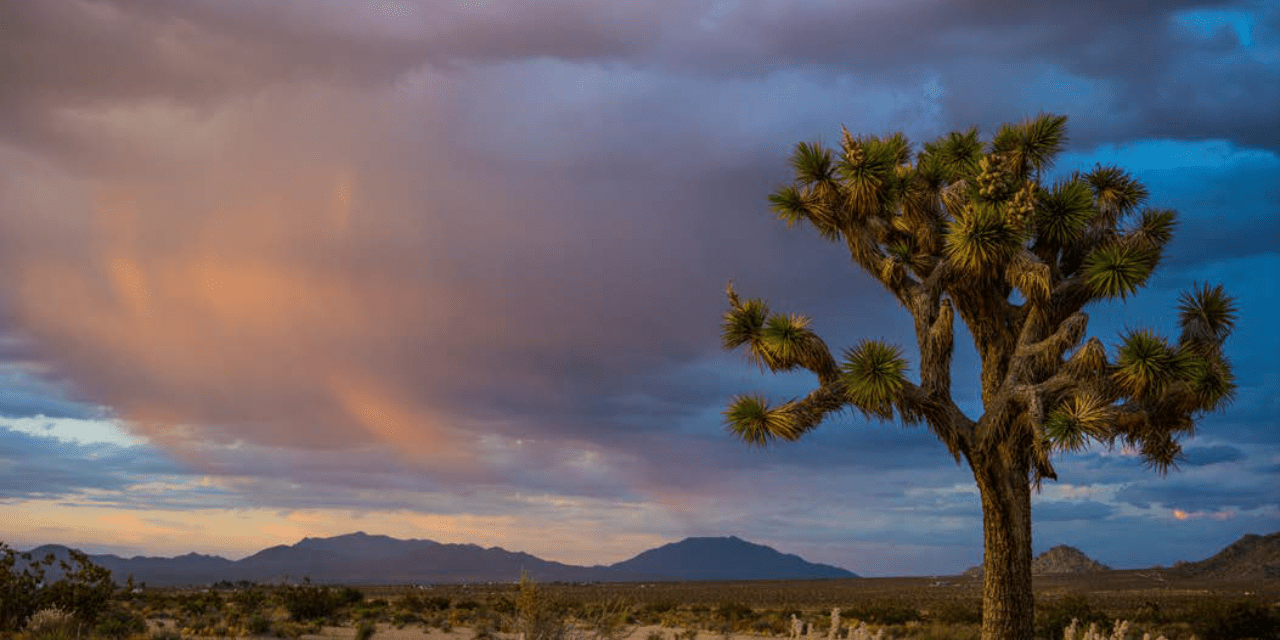

The Promise of RAIN

By Chris Clarke

Author Chris Clarke is a journalist, writer, activist, and cohost on the new podcast, “Ninety Miles from Needles.” Clarke has been interpreting the desert for more than 30 years. He is joined by co-host, Alicia Pike, a talented co-conspirator, and by the community of activists and others working to keep the desert whole.

It gets hot in the Mojave Desert.

That may seem on the face of it a platitude, like a statement about the Pontiff’s religious beliefs or the gastrointestinal whereabouts of bears. Of course the Mojave Desert is hot. It’s got Death Valley in it, where the world record more or less verified highest temperature was recorded on July 10 1913, 134° Fahrenheit, also known as 57°C.

But I’m not talking about that kind of heat. A couple or five weeks of a mere 105°F will sap even the hardiest desert rat’s reserves. We talk about the heat, about how stupid we are to have stayed, about how we ought to head for places with better weather like Montana or Alaska or Neptune.

The native mesquites in my yard spend their afternoons with their pinnate leaves folded, tiny leaflets clasping one another to keep from losing too much water to the desiccating atmosphere, branches full of tiny hands clasped in prayer.

One difference between people and mesquites: the mesquite’s prayers will be answered.

Aim the full force of the summer sun at the Mojave for long enough, saturate the land and all its suffering inhabitants with that full and constant sunlight, and eventually it — we — can absorb no more heat. We give it off. We discharge that heat into the air, we radiate it into the cloudless night sky, we glow with it. Infused with the landscape’s heat, the Mojave Desert air rises.

And as Nature, like my dog, abhors a vacuum, when the Mojave air rises skyward other air must flow in from the surroundings to replace it.

Two hundred miles south of the Mojave, past the National Park and the irrigated fields of Thermal and Mecca and Brawley and past the smog and noise of Mexicali and past the network of decaying sloughs that were once the delta of the Colorado River, a 700-mile-long water cannon points at the heart of the Mojave Desert. It is the Sea of Cortez a.k.a. the Gulf of California, an arm of the Pacific born when the Baja peninsula started peeling itself off the mainland of North America. It is rimmed with mountain ranges. Start the air rising over the Mojave and those mountains will channel marine air from the Mazatlan coast to replace it. With 700 miles of sea to give up moisture along the way, those winds get humid. They meet no resistance until well into California, when they rub up against a cluster of east-westtrending mountain ranges that block their path. The Cottonwood Mountains. The Orocopias. The Hexies. The Pintos and Little San Bernardinos.

The mountains cool the air as it flows up and over them. Some of its humidity gets squeezed out as from a kitchen sponge. One summer weekend not long ago I walked in out in the evening and watched clouds gliding over the Little San Bernardinos, gray jellyfish backlit by a lowering sun. Rain trailed from beneath them in long arcs, never reaching the ground. It is called “virga,” this frustrating evanescent rain. That evening I could smell the rain though it never landed to un-parch the ground.

Eventually none of us can take the tension any longer: the saturated air, the cacti and jackrabbits longing for even just a small drink, the desert rats cursing our bad life choices. The heat and the humidity conspire at last and real rain comes, towering thunderheads shaking the skies.

These are monsoons, the violent desert rains of summer. They are beautiful and unpredictable. They are often small, but sometimes the tension is just too much, and a huge cell will lower itself down over a broad swath of desert, dozens of miles of landscape bathed in torrent. Or hundreds. These storms rewrite the map. They lift little watercourses out of their beds, send unexpected floods through city streets. They grind down the desert plains. They sharpen the Mojave’s mountains. They toss wrack onto the highway and expose bones long thought safely buried.