Stagecoach 2024: Defining American Music in the Melting Pot of Country

By Bruce Fessier

Cover photo by Stagecoach-D. Becerra

Photos by Sandra Goodin

Stagecoach: California’s Country Music Festival was another reminder that it’s again time to ask, what is American music?

Coachella and this month’s Joshua Tree Music Festival balance eclectic international sounds with diverse bands from throughout the United States. They present distinctive artists like Mdou Moctar from Niger or Bongo Sidibe of Guinea and we receive a portal to world cultures. They tell personal stories with universal themes and bring the world closer together.

Stagecoach also showcases personal storytelling, and it now encompasses genres such as EDM and hip hop, ranchera and surf music, and dozens of forms of country. But it makes a case that the U.S. is a melting pot of cultures, so everything can be American if you wave a U.S. flag and call it country. If it doesn’t fit your stereotype of country, it’s alt-country. Or California country.

Brittney Spencer, a 35-year-old Black singer who grew singing gospel in an African Methodist Church in Baltimore and sang backup for R&B groups before moving to Nashville to pursue country, introduced a song on the last day of Stagecoach, called “Bigger Than the Song.” It referenced artists such as Reba McEntire, Aretha Franklin, Johnny and June Carter Cash, Alannis Morrisette and Janet Jackson, and Spencer said, “It’s all music, right?”

About the only American music not featured under Stagecoach’s country banner was the genre known as the Great American Songbook, which is kind of ironic.

A hundred years ago this summer, composer Jerome Kern said the epitome of American music was a Russian Jewish immigrant named Israel whose father was a cantor named Moses.

That immigrant changed his name to Irving Berlin in 1908 and wrote a song called “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” that swept the nation in 1911. The mania spread to Europe at a time when Sigmund Freud was unlocking the secrets of the subconscious and Picasso was introducing an abstract art that seemed to reflect the chaos of the modern mind. Europeans thought the quick-paced song, with its unusually long chorus kicking into the key of F from a verse in C, defined America’s frenetic culture as a new industrial power. Berlin submerged his identity as an immigrant and embraced his reputation as a voice of the American melting pot. He went on to have a unique career as a composer and lyricist of Broadway musicals such as “Annie Get Your Gun” and “Cocoanuts,” and pop songs including “God Bless America” and “White Christmas.”

Asked by writer Alexander Woolcott to explain Berlin’s place in American music, Kern told the future godfather of Palm Desert resident Bill Woolcott Marx, “Irving Berlin has no place in American music. He is American music.”

Berlin and Kern were part of an industry of songwriting factories known as Tin Pan Alley that followed a specific formula of writing lyrics and melodies. Codified by America’s first hit songwriter who published his own songs, Charles K. Harris in the 1890s, it involved studying the competition, taking note of public demand and giving the public what it wanted — with an unexpected twist, or hook, that would stick to the listener’s consciousness.

Photos by Stagecoach-A. Viscius

But even songs deemed not commercial enough for industry exploitation have thrived as pop music “alternatives.” These diverse songs, deemed more suitable for subcultures or regional audiences than songbooks for mass consumption, were so vast they had to be categorized.

In 1927, the journalist and poet Carl Sandburg compiled a book titled “The American Songbag,” featuring folk songs from dozens of American regions that he categorized into genres, such as “minstrel songs,” “hobo songs,” “blues, mellows, ballets,” “Mexican border songs” and “prison and jail songs.” The compendium’s influence extended over six decades to artists such as Cab Calloway, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen.

Today, Beyoncé sings about the practice of gatekeepers deciding what songs are fit for national dissemination in her genre-busting country album, “Cowboy Carter.” She calls genres “a funny little concept” in her song, “Ya Ya,” featuring strains of the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations” and Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made For Walking.”

Genre songs actually proved massively popular in 1920s recordings. But blues releases by Black artists were categorized as race” records and rural discs by white performers were called “hillbilly” songs. These “less-elite” artists were even given separate record labels by their recording companies to distinguish them from more “literate” white artists, whose popularity was measured by how many copies of sheet music they could sell for their publishers.

Photos by Stagecoach-C. Kenyon

The same year “The American Songbag,” was released, the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers were anointed as royalty of hillbilly music after being recorded on consecutive days by a “song collector” named Ralph Peer. Like Stephen Foster seven decades earlier, these white artists were influenced by the same Black spirituals and work songs that inspired Black genre artists.

Musicologist Santi Elijah Holley wrote in The Atlantic in 2022 that the Carter Family was influenced by Lesley Riddle, a Black guitarist who taught Maybelle Carter a modern style of lead guitar-playing and helped A.P. Carter find and adapt the traditional “Wabash Cannonball.” The Carter Family sang spirituals and hymns such as “Keep on the Sunny Side” and “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” which was included in Sandburg’s “The American Songbag.”

Rodgers, who recorded “Blue Yodel No. 9” with Black jazz pioneers Louis Armstrong on trumpet and Lil Hardin on piano, started his professional career singing in Blackface with a traveling medicine show. He played an amalgam of blues and hillbilly music and influenced generations of musicians in other genres. His 1928 recording of “Waiting For A Train” was covered by Gene Autry, who transformed hillbilly into “Western” music in the 1930s as Hollywood’s most popular singing cowboy. Rocker Boz Scaggs recorded it in 1969 with Duane Allman, who pioneered Southern rock with the Allman Brothers, which continues to influence modern country today.

Photos by Stagecoach-D. Becerra

The Stagecoach big picture

Stagecoach reflected where country came from, where it is now, where it’s going and how it became America’s music April 26-28 at the Empire Polo Club in Indio. It was a three-act opera with a prelude and an encore.

The prelude began early the first day when Vincent Neil Emerson, a Texan who is part Choctaw-Apache, sang “25 & Wastin’ Time” from the acclaimed streaming series, “Reservation Dogs.” It was country music relatable to cowboys and Indians. How great is that? The set’s highlight was “Little Wolf’s Invincible Yellow Medicine Paint,” about indigenous life on the plains, where Emerson sings over and over, “Everything is dead.”

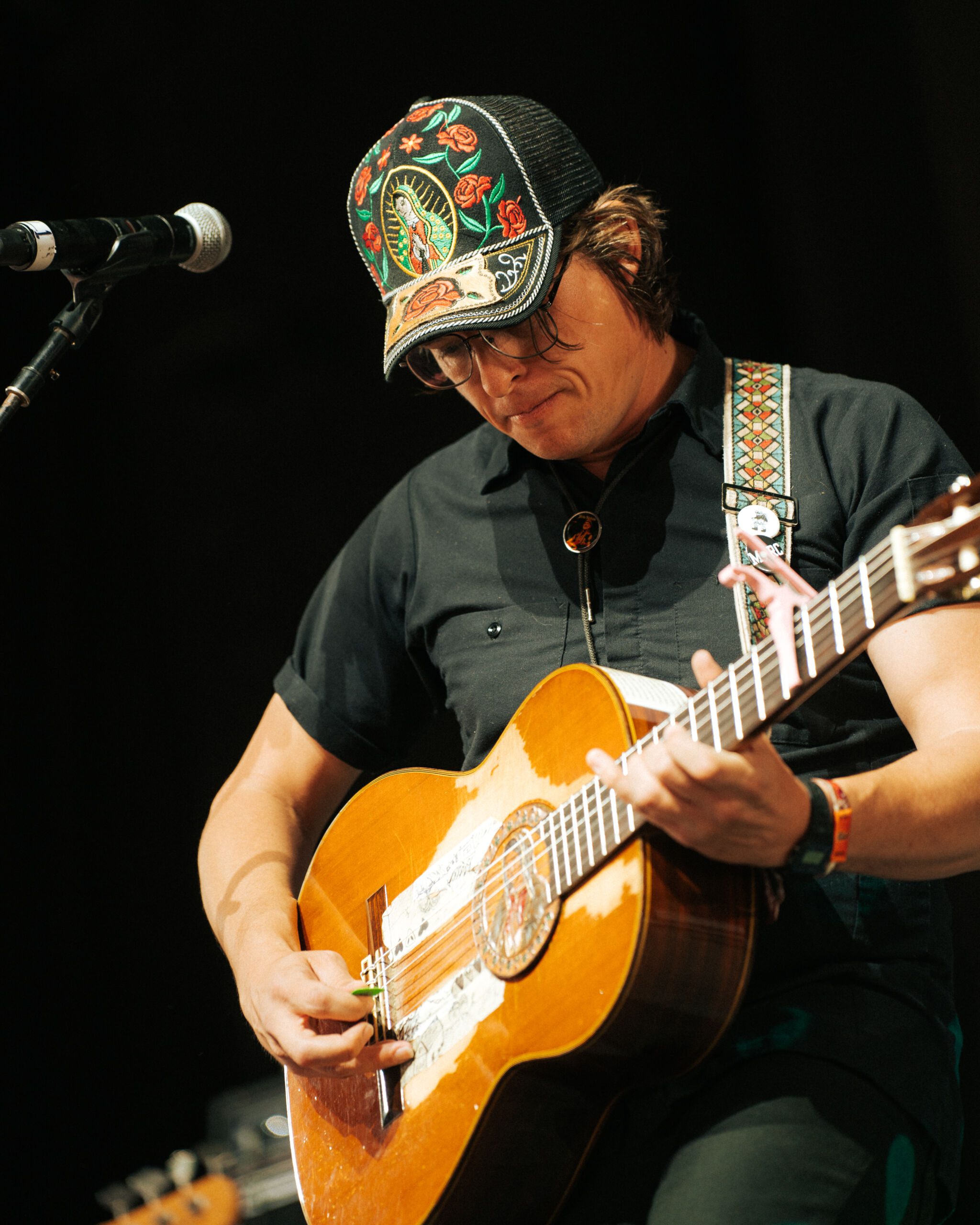

Act I was about where country music has been. Dwight Yoakam actually opened his evening set with “Keep on the Sunny Side,” taking us all the way back to the Carter Family. Then Eric Church took us even farther back.

Church, making his third headlining appearance after performing as an opening act at the first Stagecoach, has been criticized for not playing a showcase of hits. But he delivered a brave act of performance art that should be applauded for not following a Tin Pan Alley formula, for conceiving and realizing an artistic vision that fit perfectly into a broader message.

Photos by Sandra Goodin

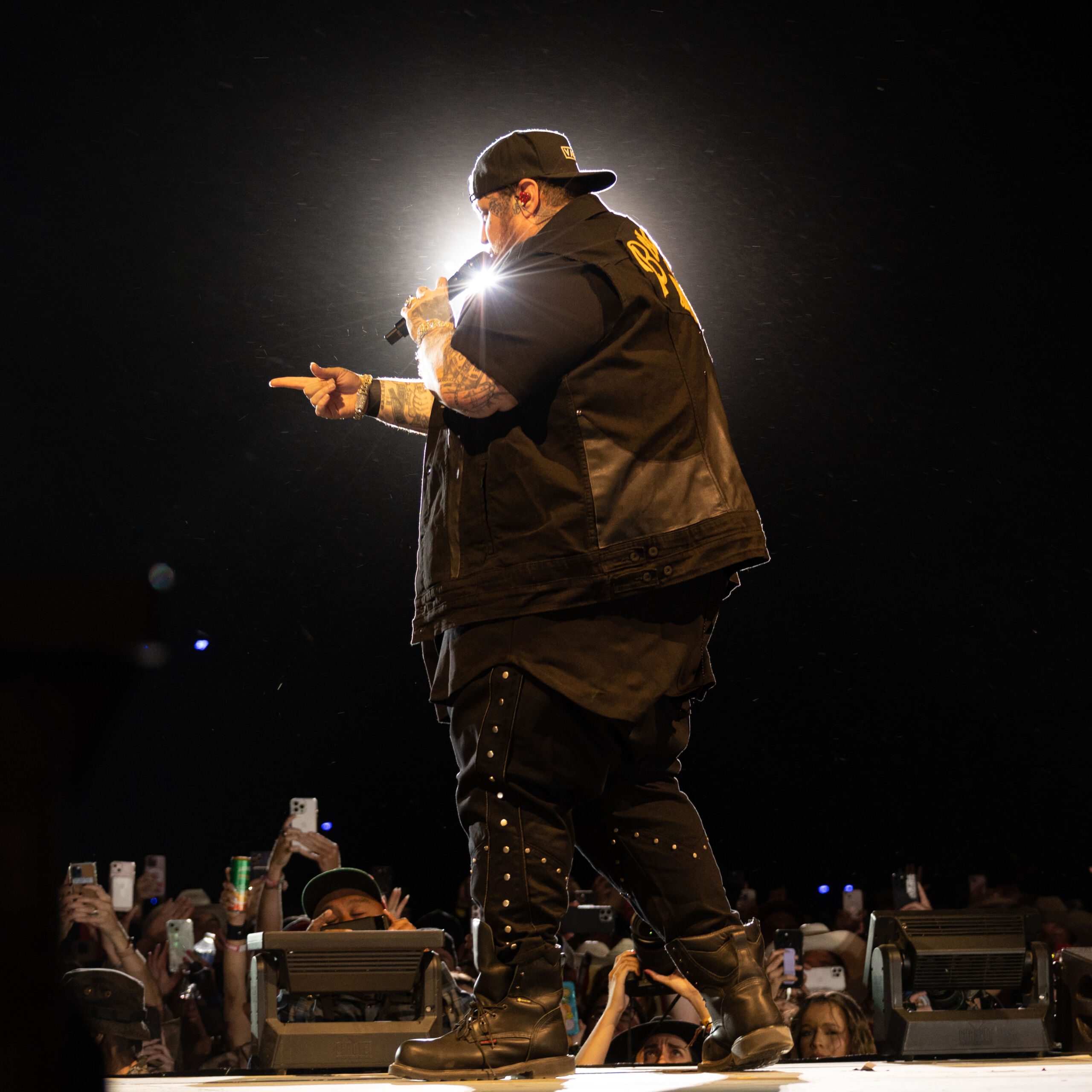

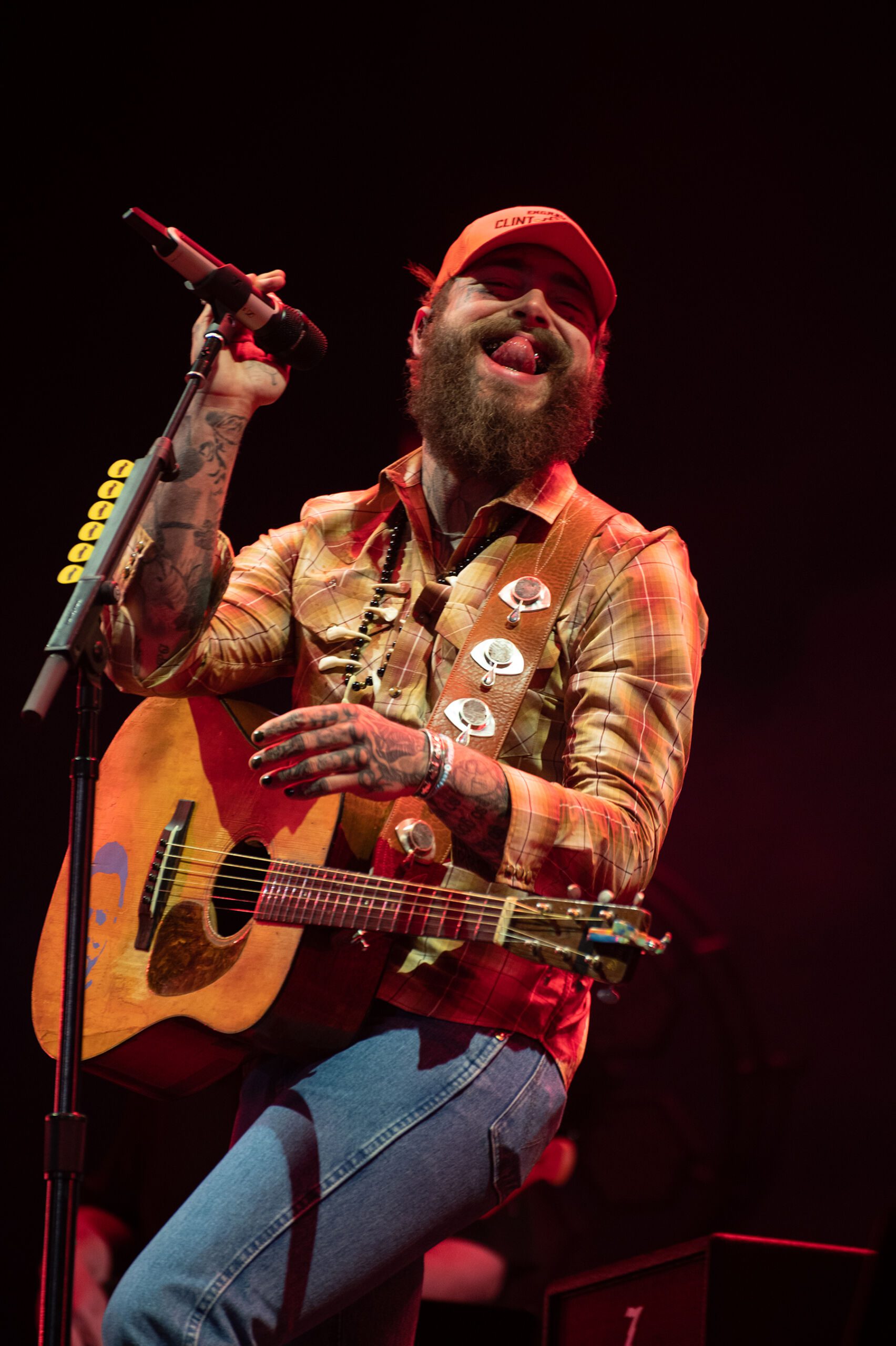

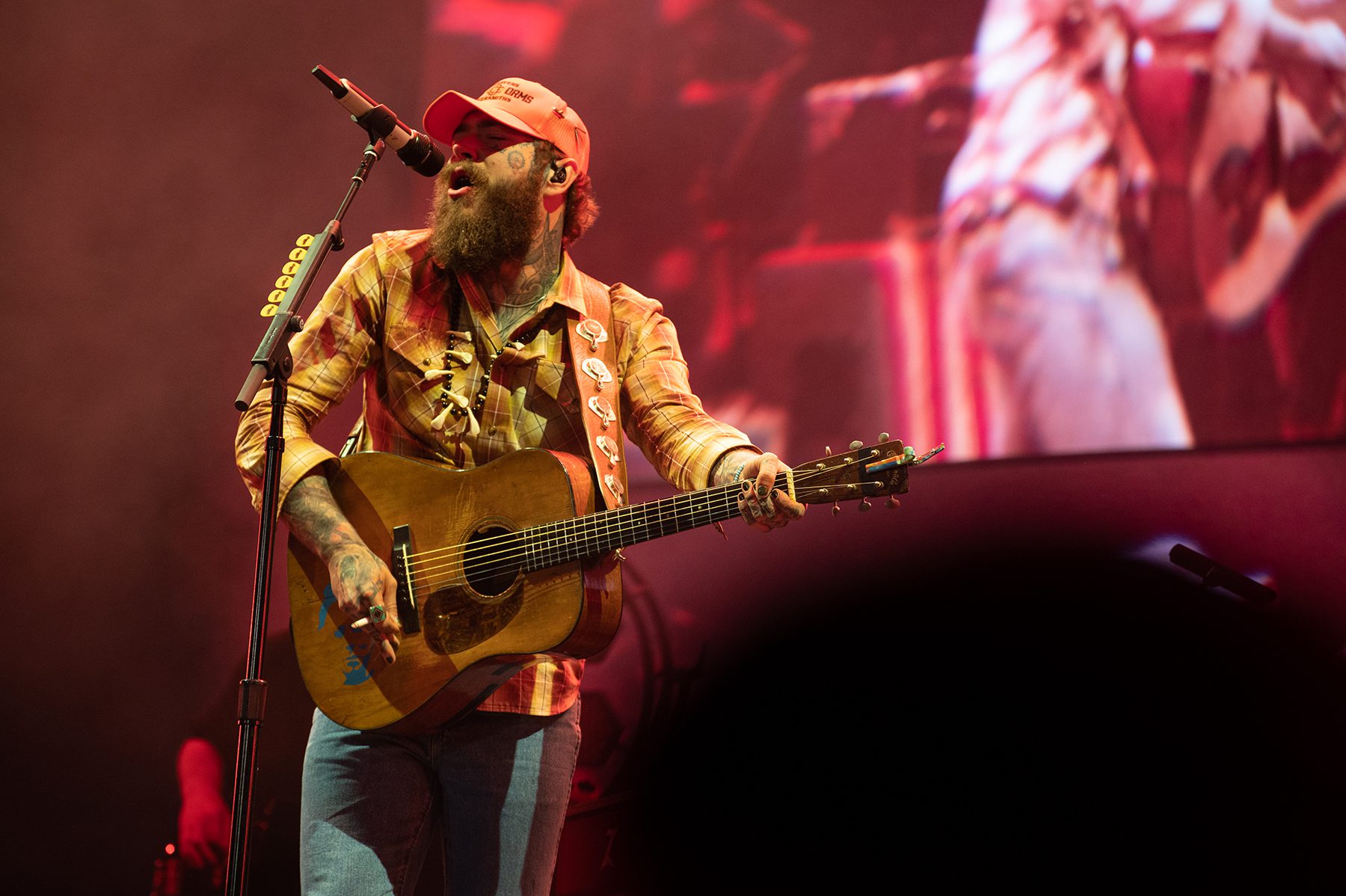

Country now embraces all forms of music, as Jelly Roll proved with his compelling set just before Church walked onto a stage built to look and sound like a real church, with a gospel choir added as the set went on. He demonstrated with old spirituals like “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “This Little Light of Mine” and “When the Saints Go Marching In” that American music started in Black churches. Then, by singing more contemporary gospel music, like the Impressions’ “People Get Ready,” Al Green’s “Take Me to the River” and the Edwin Hawkins’ Singers “Oh Happy Day,” he showed that American music still has church roots. And by playing church-evolved secular songs like “Stand By Me,” “I Am I Said” and “(Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher and Higher,” plus purely secular music like “Danny’s Song” by Loggins & Messina, “Gin and Juice” by Snoop Dogg and “California Love” by 2Pac, he expressed that it’s all church because American music comes from the church. Or was he saying it’s all Eric Church?

He brilliantly slipped in his own songs that fit his theme, including “Like Jesus Does” and “Country Music Jesus.” It was the height of artistic achievement to bookend his set with “Mistress Named Music” and to end with his biggest hit, “Springsteen,” about another artist who explored similar roots music in his “Seeger Sessions.”

If I were wearing a cowboy hat, I’d take it off for Eric Church.

Photo by Stagecoach-D. Ernst

The road to where we are

Act II was about how country got to where it is today. Obviously, there were no Elvis Presley tribute artists. Ray Charles couldn’t show how country could be applied to soul. No one could replicate the storytelling power of Johnny Cash and his stage magic with June Carter Cash.

But artists like Stephen Wilson Jr., Drayton Farley and Charley Crockett personified the personal, vulnerable storytelling style of Hank Williams and Merle Haggard, with Crockett addressing the country nation with his plaintive “America” (“America, I love ya, and I fear you sometimes”). Trampled By Turtles represented the old-timey “hillbilly” bands that didn’t include drums with one of the most musically taut sets of the weekend. Asleep at the Wheel conveyed the Western swing of Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys — the World War II-era big band that introduced drums and a horn section to country. It also reflected the psychedelic country of Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen with its version of “Hot Rod Lincoln.”

Photos by Stagecoach-J. Mulka

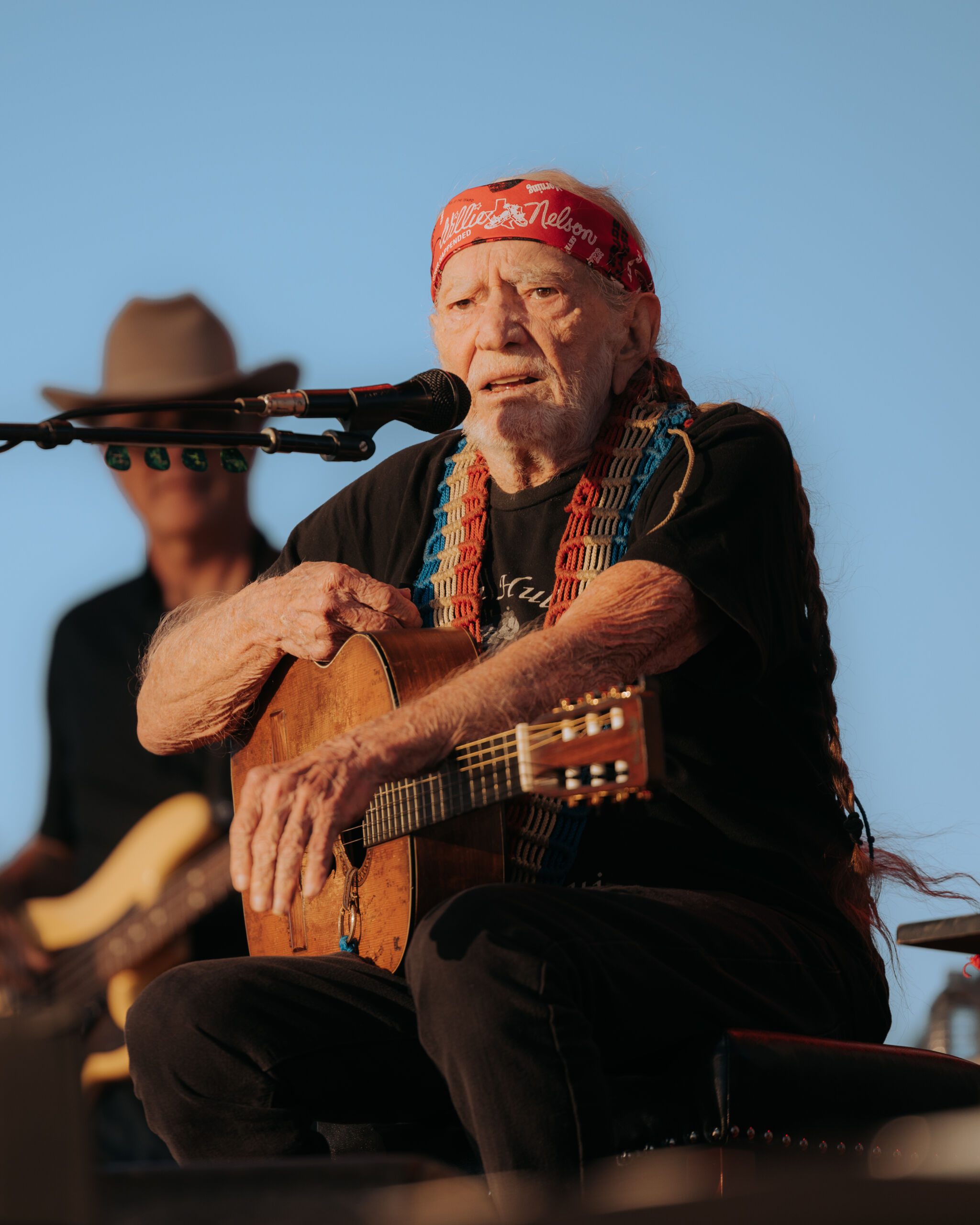

There was no more authentic reminder of a change in country music than Willie Nelson’s set with his son, Lukas, and his traveling musical family. Sitting on stage with his shaggy white hair symbolically blowing in the wind, Willie sang hits that didn’t just represent outlaw country. He was outlaw country. It was like sitting around a campfire with Abraham Lincoln listening to this majestic figure in American history tell his own stories.

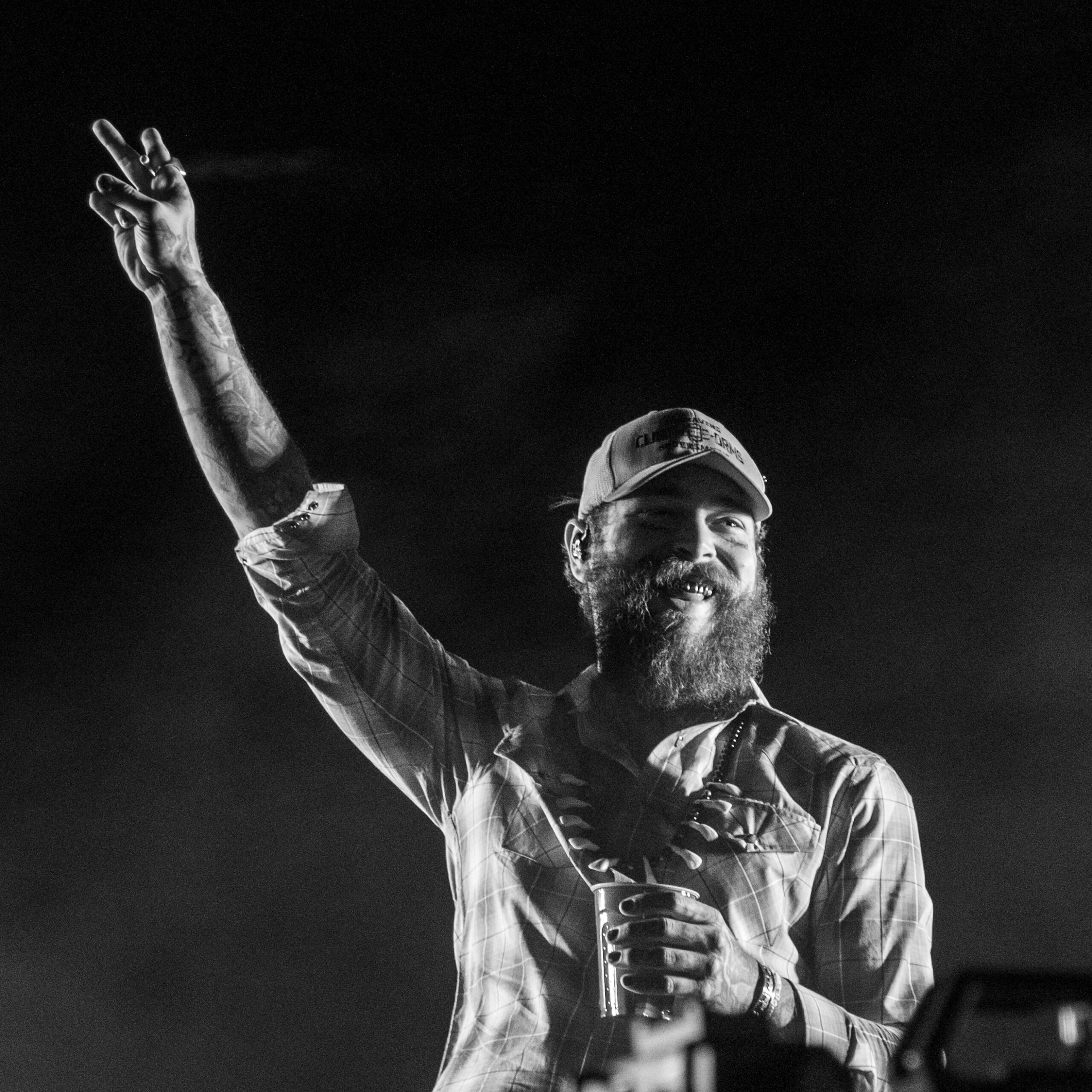

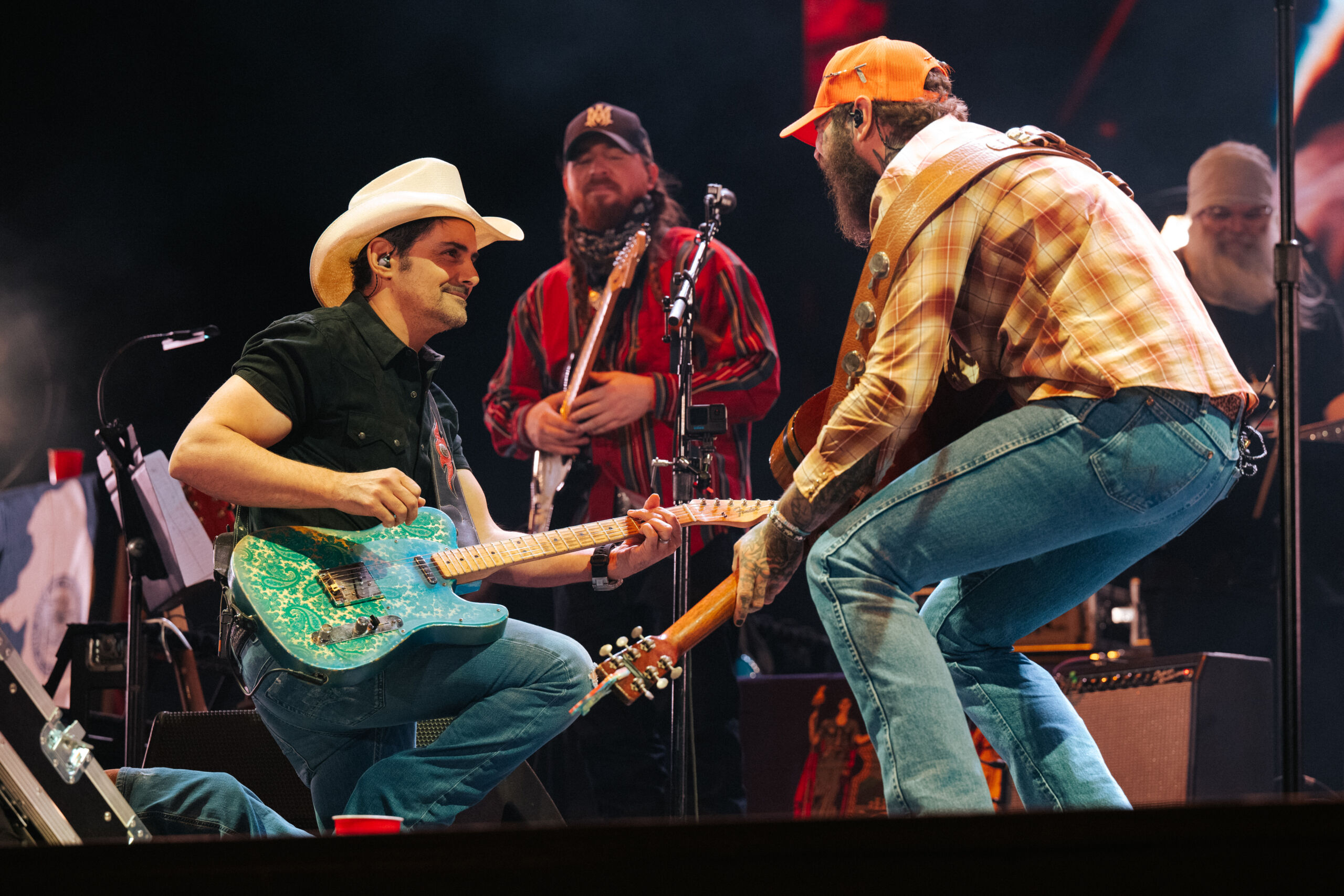

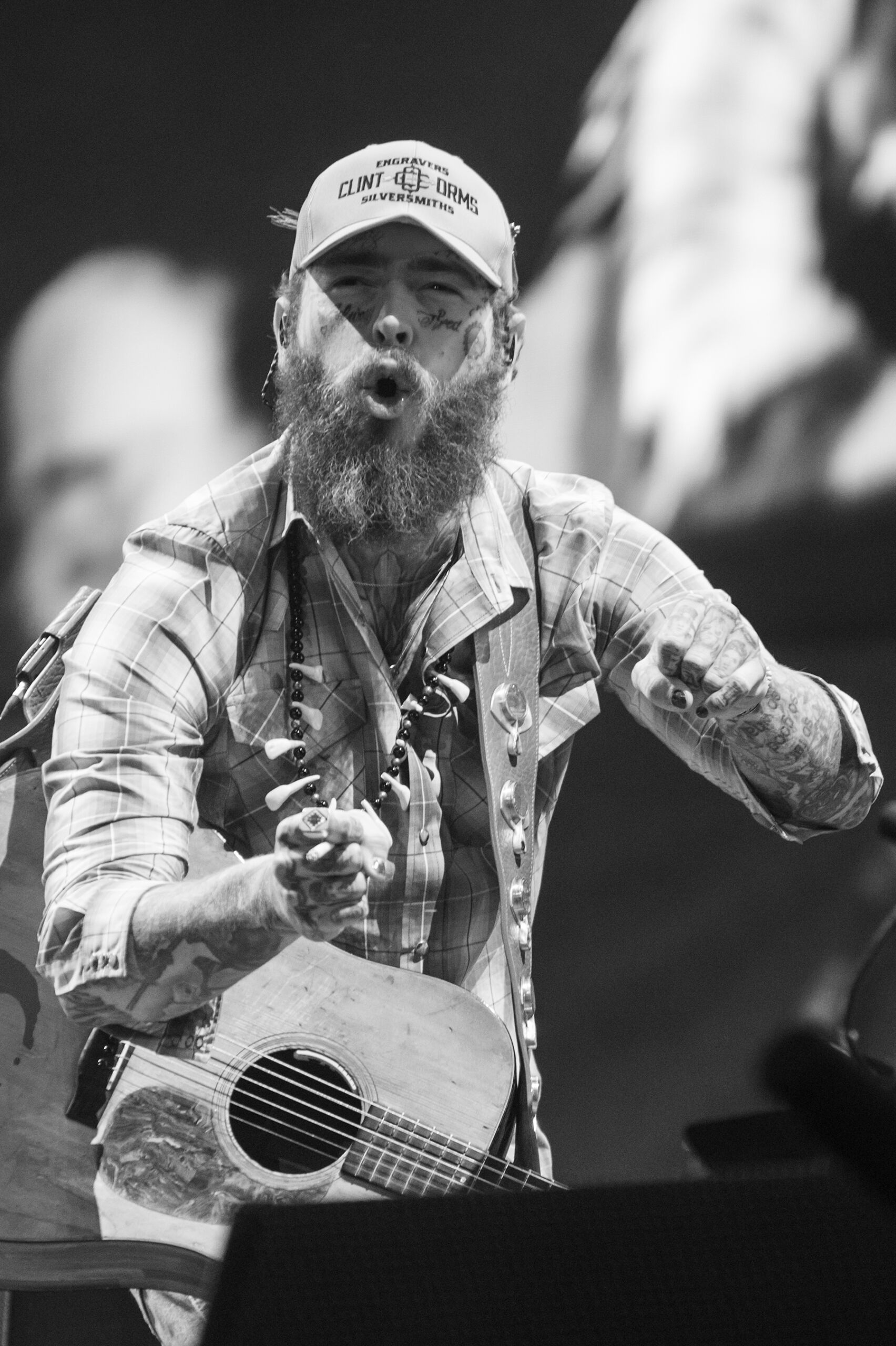

Not many people could follow the 91-year-old Nelson, but rap-rocker Post Malone did just that, submerging his contemporary identity like Jamie Foxx in “Ray” to represent ’90s country music. He was compelling and authentic in songs like “Three Wooden Crosses” by Randy Travis, “Who’s Your Daddy” by Toby Keith and three songs with Brad Paisley, who he let shine on guitar despite his own guitar prowess.

There was probably no better interface of generational talent than Reba McEntire joining Miranda Lambert for the culmination of how we got to this point in country. Lambert conjured aural images of Dolly Parton with her 2022 release, “Geraldine” (“You’re trailer park pretty, but you’re never gonna be Jolene”). She also appeared at the first Stagecoach and she’ll be remembered for bringing modern country production to the neo-country music that McEntire and George Strait pioneered. So having McEntire join her for a duet of McEntire’s “Fancy,” plus two of her own hits, was a moment in history.

Representing American music

Act III was about where country music is today, as a representative of American music, and Brittney Spencer exemplified its inclusiveness by performing in the alt-country Palomino tent and then playing for dancing in the new Bud Light Backyard tent.

But a bigger indication of country’s growth into contemporary pop was happening at Diplo’s larger Honkytonk dance floor. At 5:15 p.m., the line to get into see the 45-minute DJ set of James Kennedy, a cast member of the reality show, “Vanderpump Rules,” was one hour long. That meant many people were probably waiting to see the next DJs, Diplo and Marshmello, two of the biggest Coachella attractions from the height of the EDM movement in the mid-2010s.

Photo by Stagecoach-S. Hutchinson

Clint Black, making his first Stagecoach appearance despite symbolizing the post-George Strait neo-traditional ’90s style, checked a box of what country still represents in America. Pam Tillis fortified that by name-shouting her father, the stuttering classic country balladeer Mel Tillis, while proving her meddle as her own woman with her own hits from the ’90s and 2000s.

But the biggest expansion of country’s growing representation was the appearance of Mike Love and his son, Christian, in cowboy hats while their backdrop proclaimed in large type that the Beach Boys are “America’s band.” John Stamos also played the entire set as a reminder that he regularly performed with the Beach Boys before starring in TV’s “Full House.”

No one argued or even wondered what a surf band was doing at California’s country festival. The crowd noise level was beyond the proverbial “11” decibels. Millennials and Gen Zers were singing along to songs that became part of the national consciousness 60 years ago. The visuals of the Beach Boys’ history, juxtaposed against other images of ’60s pop culture mythology, including Marilyn Monroe, overwhelmed any memories of the legal in-fighting between Mike Love and the band’s founding genius, Brian Wilson, now suffering from dementia. It was like watching a slide show of Andy Warhol images mythologizing the memory of the Beach Boys as an act that came out the other side as America’s country band.

The Beach Boys set went beyond its allotted time, which cut into our time to watch HARDY on the Mane Stage. But we got to see the 33-year-old arena star bring Act III to a close with songs equating country music with God and America. He sang Blake Shelton’s “God’s Country” with the lyrics, “Right outside of this one-church town… Got a deed to the land, but it ain’t my ground. This is God’s country.” Then he sang “Unapologetically Country As Hell” with visuals calling to mind the Fourth of July.

Photos by Sandra Goodin

That’s when the curtain should have come down as thousands cheered, like in the racially groundbreaking 1933 Irving Berlin revue of that name. But then headliner Morgan Wallen came on for the encore.

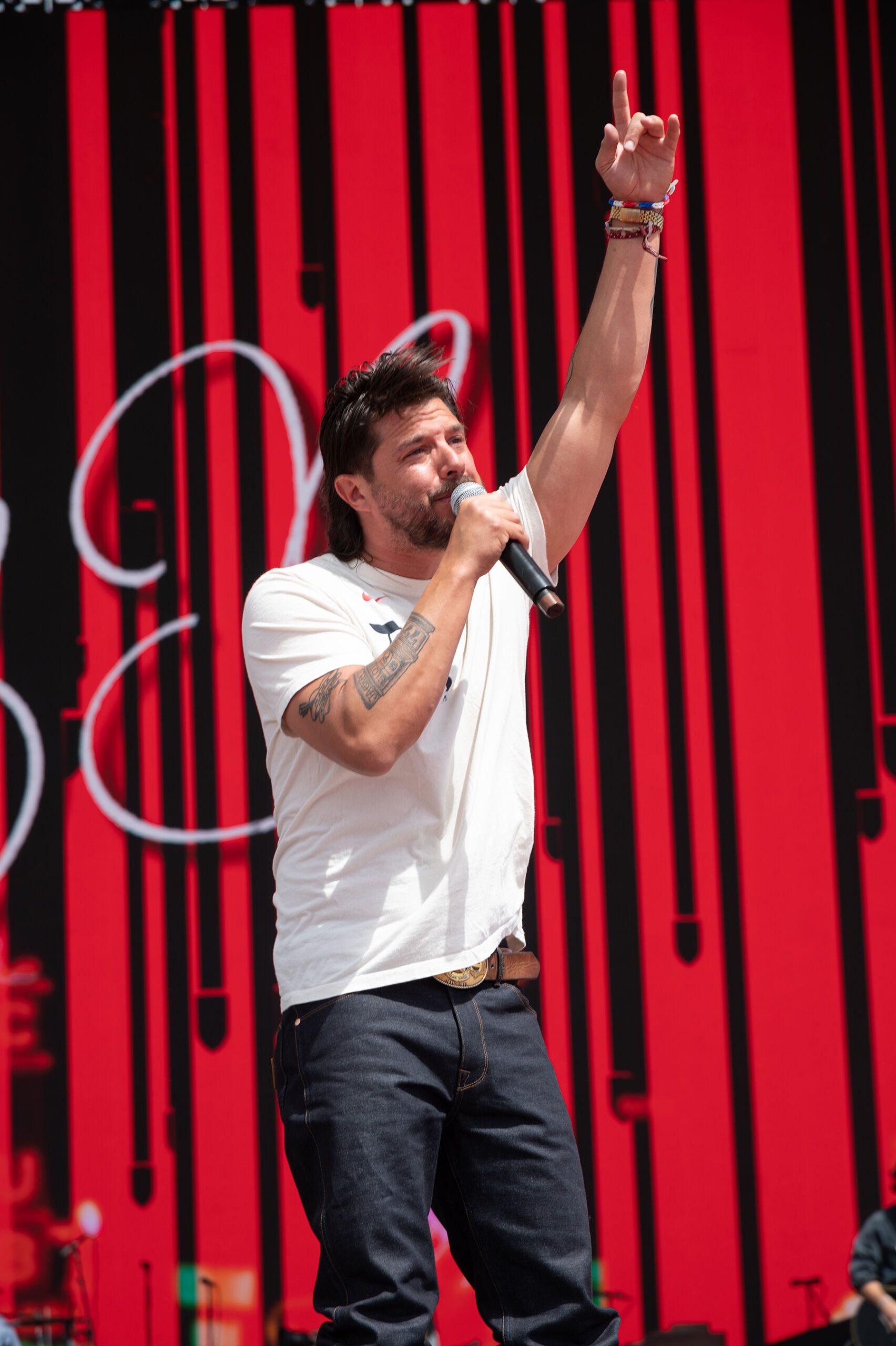

Wallen is country’s bad boy de jure, thanks to some reckless behavior that probably would have passed unnoticed if he wasn’t so popular. But he represented the part of America that prizes the individual who takes on institutional predators and succeeds by doing things his way.

There were the homages to God and country, like “Man Made A Bar,” where he sings, “God made a man, and man got lonely… So God made a girl, His best work of art. But He didn’t make no place to go when she breaks your heart. So man made a bar.”

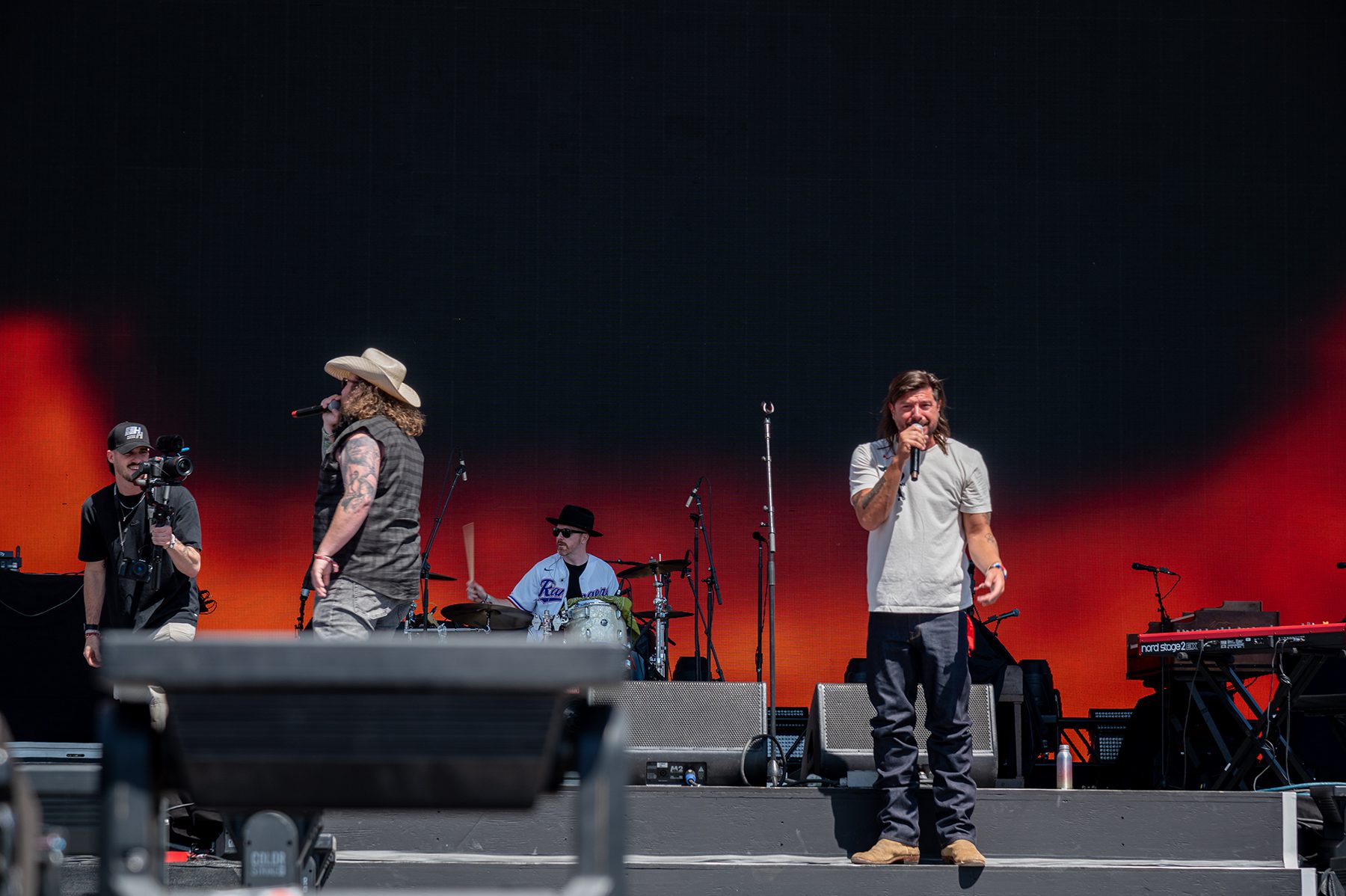

Like those big Broadway shows when the stars return for a production number, Wallen’s set featured Stagecoach stars in four straight numbers. HARDY sat in on his original, “He Went to Jared.” Baily Zimmerman did a duet on “Up Down.” Ernest joined Wallen for “Cowgirls,” and Eric Church, being the gospel fan he is, came on for “Man Made A Bar.” Post Malone joined in on the second encore, “I Had Some Help.”

Wallen saved his final encore for “The Way I Talk,” which obviously addresses the time he got caught using the “N word.” It asserts, “The man upstairs gets it, so I ain’t tryna a fix it. No, I can’t hide it. I don’t fight it. I just roll with it.”

That’s a man saying, “I’m flawed, but I am who I am.” That’s an individual asserting his right to be comfortable in his own skin. And as John Mellencamp once said, ain’t that America?”

Bruce Fessier was inducted into the inaugural class of the Coachella Valley Media Hall of Fame. Contact him at jbfess@gmail.com or facebook.com/bruce.fessier